An epidemiological analysis of the events surrounding a new disease in abalone - Technical Summary

This report provides an epidemiological analysis of the events surrounding an outbreak of a new disease in farmed and wild abalone in Victoria that began in December 2005.

The most likely cause of this disease is a herpes-like virus. The epidemiological investigation identified the most likely source of the virus as live wild abalone that were brought onto one of the affected farms at the start of the outbreak.

No possible link to an exotic source of the virus has been identified through the investigation conducted for this report and an exotic source of this virus is considered highly unlikely. The report also concludes that it is highly improbable that feed was a source of the virus, and that it was most likely that the virus was introduced onto the index farm in wild broodstock, in which the disease was endemic.

This virus and this disease have never before been seen on abalone farms in Australia. This does not mean that this is the first time disease caused by this virus has occurred in Australia. As in many aquaculture industries, infectious agents present in wild animals are often only identified when those animals are farmed and closely monitored.

Very little is currently known about this virus, including how it infects abalone, what the infectious dose is, how long it survives outside the host (and how long it survives in the water column) and whether or not healthy abalone can carry the virus. Herpes viruses in general, however, are known for their ability to cause latent (silent) infection in otherwise healthy animals.

The diagnostic feature currently used to identify this disease is the histopathological finding of ganglioneuritis, or inflammation of the nerves. Electron microscopy (EM) has been used to confirm the presence of herpes-like virus in nerves of affected abalone, though EM is not used as a routine method of diagnosis.

While histopathology and electron microscopy have been highly useful diagnostic tools in the initial outbreak investigation of this disease, they have limitations e.g. neither the sensitivity and specificity of either test is accurately known.

There are currently no diagnostic tools or methods available to identify this virus if there are no pathological changes in the abalone (e.g. if the virus is latent in the abalone).

There are also no tools to quantify the level of this virus in infectious material. These tools are essential to get more understanding about this disease.

A recently conducted national survey of commercially exploited abalone species in Australia did not detect any evidence of this virus in over 3000 abalone that were sampled as part of this survey. However, if the virus was in a latent state it would not have been detected in this survey even if present.

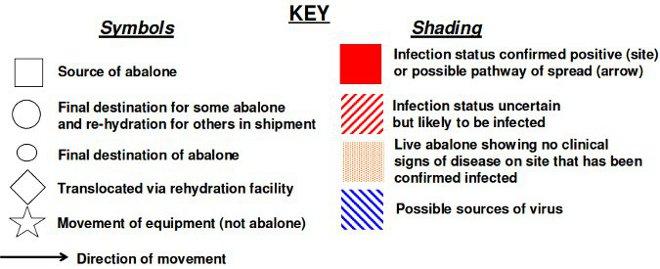

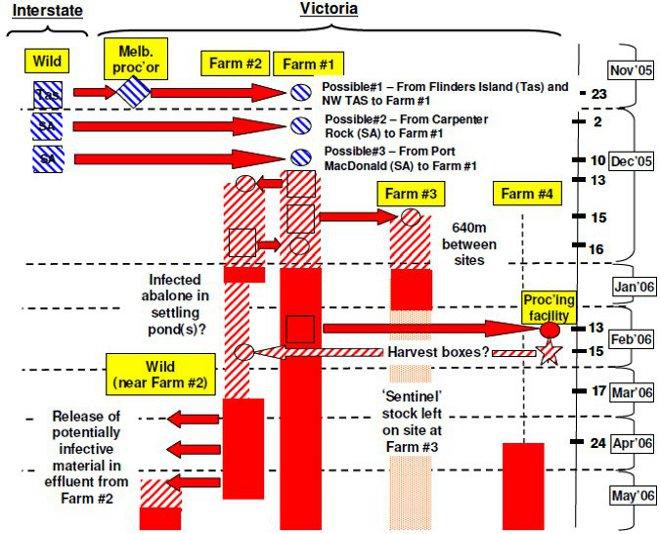

Figure 1 summarises, in schematic form, a flow chart identifying the main events of the outbreak. A full explanation of each of these events is provided in the main part of the report.

Figure 1 Summary flow chart of events showing movements of abalone and equipment from November 2005 until May 2006 ( Refer to the end for a key to symbols and shading )

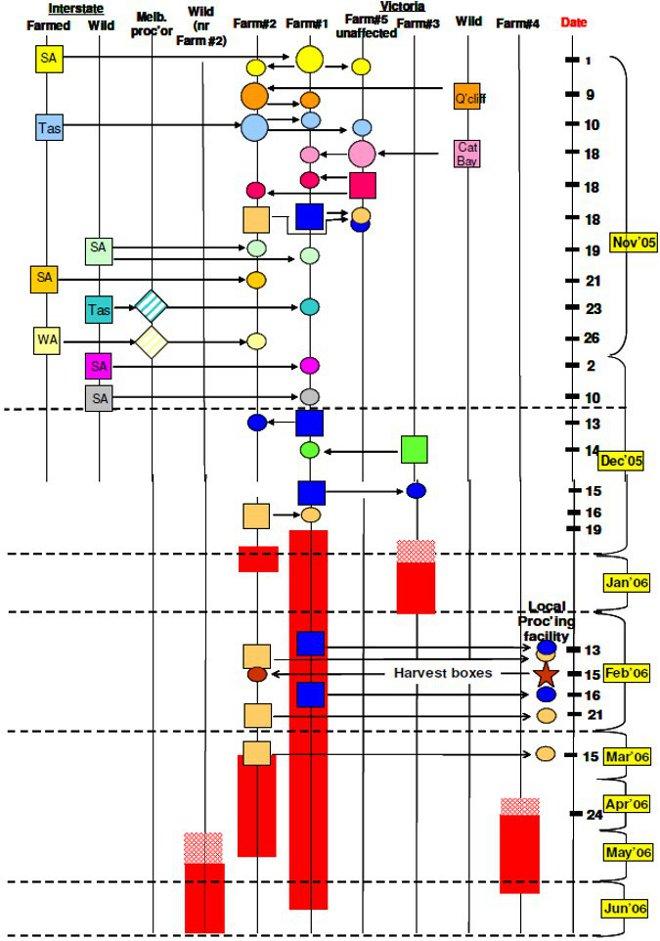

Figure 2 summarises, in schematic form, a 'best fit' scenario of the outbreak based on the epidemiological investigation carried out for this report. This 'best fit' scenario is based on the current knowledge of the outbreak and the virus, which at this stage is limited. New knowledge may alter this 'best fit' scenario.

Figure 2 "Best fit" scenario identifying most probable disease pathways given current knowledge on the outbreak and the disease ( Refer to the end for a key to symbols and shading )

The following are the conclusions from which this 'best fit' scenario has been constructed:

The first case of this disease on an abalone farm most likely occurred in early December, 2005 on Farm 1 This is based on the epidemiological investigation which included examining such factors as patterns of spread, timing of movements and linkages between affected populations of abalone.

The three most likely movements of wild abalone that are considered as possible sources of the virus, based on the timing of events and the history of movements are:

- Wild abalone collected from the Port MacDonald area in South Australia and brought onto Farm 1 on December 2nd, 2005. Water temperatures around Port MacDonald during December, 2005 and January, 2006 were approximately 1 to 2ºC higher then average for this time of the year

- Wild abalone collected from the Carpenter Rocks area in South Australia and brought onto Farm 1 on December 10th, 2005. Carpenter Rocks is located approximately 35km from Port MacDonald

- Wild abalone collected from Flinders Island and north west Tasmania brought onto Farm 1 (via a rehydration facility) on November 23rd, 2005.

The source of the virus that caused the first outbreak of the disease at Farm 2 was most likely through infected abalone translocated from Farm 1 to Farm 2 on December 13th, 2005.

The source of the virus that caused the outbreak of the disease at Farm 3 was most likely though infected abalone translocated from Farm 1 to Farm 3 on December 16th, 2005.

Possible pathways as to how the disease re-emerged at Farm 2 are:

- The disease never left Farm 2 but remained in abalone in effluent drains and settling ponds on the farm. Infectious material was transferred back to abalone in grow out tanks via a vector (e.g. rodents); or

- The disease was brought back onto the farm through infected harvesting boxes.

It is not clear when the disease first affected abalone at Farm 4 and hence it is difficult to identify the most likely way this farm became infected. Farm 4 is however, located approximately 640 metres from Farm 3.

There are a number of pathways identified in the report whereby wild abalone in the vicinity of the effluent discharge area of Farm 2 could have been exposed to virus being released in effluent water.

Whether or not disease may have resulted from that exposure is difficult to say given the lack of quantifiable information in this area. There is also though not enough information to say that possible exposure would not have resulted in disease.

As the most likely source of this virus is from wild abalone, wild abalone may have an inherent resistance to it. Apparently healthy abalone were noted in the vicinity of the effluent discharge area of Farm 2 in July, 2006. This is an area where disease is known to have occurred. There currently is though no tool to determine whether or not these abalone have been exposed to virus.

A number of possible pathways whereby the disease could spread in the wild are identified. These include through virus being shed from infected abalone into the water column (direct exposure), by direct physical contact between wild abalone, by abalone grazing on weed or algae which has infectious material on it (e.g. mucous) or through dead or dying abalone being moved by seals and fish. There is no information currently available to quantify or qualify such pathways.

Some commercial diving activity occurred around Farm 2 in May, 2006 prior to the Control Area being declared in June, 2006. Movement with infected gear could potentially be a pathway whereby disease could spread, though commercial divers had by this time been instructed in biosecurity measures to be taken to minimise this risk.