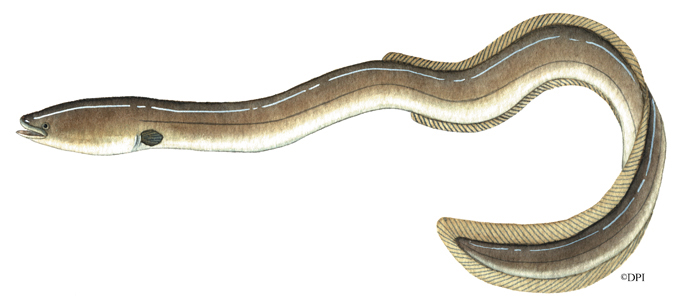

Short-finned eel

| Common Name: | Short-finned eel |

| Other Name/s: | Silver eel, yellow eel |

| Family: | Anguillidae |

| Scientific Name: | Anguilla australis |

| Origin: | Native |

Description

Long, tubular body with dorsal, tail and anal fins forming one fin. Small gill opening on each side of the head. Large mouth extending to below the small eye. vertical gill openings. Dorsal fin begins just forward of the anal fin. Back and sides may be olive-green or vary from pale green to olive-brown, sometimes with coppery tints above and silvery sides. Belly is greyish to silvery-white. Fin colour is dark like the back.

Distribution

Common and widespread in Victoria south of the Great Dividing Range, occurring occasionally in northern streams draining into the Murray River.

Habitat

Prefers low-lying swampy streams and lagoons. Although it occurs in a wide variety of habitats it is essentially a still-water species. Common in many southern Victorian lakes. Studies of tagged eels indicate that maturing adults in freshwater establish home ranges of about 400 m.

Brief Biology

Known to occur in Victoria to 1.1 m and 6.8 kg, but is usually smaller. Appears to go into hibernation if water temperature falls below 10°C. Hibernating or otherwise there are records of eels going without food for up to 10 months. Opportunistic omnivore although it is primarily carnivorous.

Adult eels are known to take fish of various types, worms, insects, small crustaceans, molluscs and water plants. Feeding appears to follow a seasonal pattern, being most intense at night in shoreline shallows during spring and summer. Mature migrating adults vary from 6 to 24 years of age, spending up to 14 years in freshwater. Spends most of its life cycle in freshwater and migrates downstream to spawn at sea when sexually mature.

General information for Victorian freshwater eel species

One of the most interesting features of Victorian freshwater eels, is the huge migration they make to a spot somewhere south east of New Guinea in the Coral Sea. This is the sole spawning site for all Australian and New Zealand freshwater eels, with some eels having to travel in excess of 3,000 kilometres to get there.

They begin their lives at this spawning site, at a depth of 200 m, as tiny transparent larvae. They are carried southwards by the ocean currents that parallel the east coast of Australia, and swing east past Tasmania and then north to New Zealand. Along the way, they feed on microscopic organisms and develop into transparent, leaf-shaped larvae or leptocephali and eventually metamorphose into 'glass eels' which are eel-shaped, but extremely small and still transparent. At this stage, they move closer to land and commence migrating towards estuaries.

The ability of eels to reach Victorian waters is believed to be dependent on the formation of relatively erratic eddy currents, which split off from the main east Australian current and transport the developing larvae through Bass Strait. These currents break down before they reach the mouth of the Murray River and this is the reason for the natural absence of eels in the Murray River and its tributaries north of the Great Dividing Range. In years when these currents are strong, there is a massive arrival of glass eels along the Victorian coast, but in some years the currents are weak and very few glass eels arrive. Their attraction to an estuary depends on the ability of glass eels to detect freshwater flows from rivers. In years when river flows are low and estuaries may even be closed, recruitment of glass eels is correspondingly reduced or may be zero.

Short-finned glass eels enter estuaries mainly during mid winter to late spring, while long-finned glass eels enter estuaries from mid summer to late autumn. Short-finned eels spread along the entire Victoria coastline, while long finned eels are only found east of Wilsons Promontory. Some glass eels will quickly pass through the estuary and migrate upstream and others will remain in the estuaries for some time. They all gradually take on the dark pigmentation of freshwater eels and at this time they are known as elvers. Some elvers remain in the estuary until they mature, but most will migrate upstream in secondary migrations, known as "eel fares", which involve glass eels and elvers of several age groups moving inland into rivers, creeks, lakes and swamps.

Male short-finned eels generally mature when eight to twelve years of age, whilst females mature in ten to twenty years and long-finned eels can take double this time to mature. At maturity, eels undergo a number of changes in preparation for the spawning migration. After a period of voracious feeding, and significant growth, their eyes become larger and their skin takes on a silvery appearance. Internally, their gonads begin to develop and their digestive system closes down and starts to degenerate, Now known as 'silver' eels, they migrate back to the sea during late summer and autumn. They quickly move into deeper water and in total darkness swim north against the current to reach the Coral Sea. By the time they arrive, they have basically used up all their energy resources and are little more than a skeleton with gonads. They spawn and die and their young commence the cycle over again.

The commercial fishery for eels utilises both species, in coastal waters from Mallacoota to Portland. However, the bulk of the activity is based on short-finned eels and takes place in the lakes and wetlands of the Western District. Much of the production depends on the eel fishers translocating large numbers of small eels from waters where conditions for growth are poor, to more favourable areas where they can grow to reach commercial size and condition over a number of years.

With a fishery that involves such a slow growth rate, a long life cycle, and where recruitment is so erratic and variable, it would be very easy for the stock to be overfished and for the fishery to collapse for long periods. This has not happened because entry to the fishery is tightly controlled, and the best waters have been exclusively allocated to individual fishers.

This encourages each operator to fish their water conservatively and ensures that, if they exercise restraint, they will be the one getting the benefit of it. In addition to this, there are many coastal streams that are totally closed to commercial eel fishing. Although this was done initially to ensure that platypus in these waters were not caught in nets, it also ensures that there is always an unexploited area to provide spawning stock to return to the sea. There is a huge unsatisfied world demand for glass eels for aquaculture, and without tight control, the Australian resource could be quickly stripped to satisfy European and Asian requirements.

While the average angler may have little regard for the common eel, it certainly has a fascinating life cycle, and supports a significant and productive commercial fishery. When it is also considered how intensively anglers use many of the waters important to the commercial eel fishery, there has been a commendable lack of conflict between the two groups.