Mallacoota Management Plan

Fisheries Victoria Management Report Series No. 36

September 2006

Executive Summary

The purpose of the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve Management Plan (MIFRMP) is to specify the objectives, strategies and performance measures for managing fishing activities within the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve.

The MIFRMP has been prepared under the requirements of the Victorian Fisheries Act 1995 and has been developed in accordance with gazetted Ministerial guidelines. The MIFRMP prescribes fishery management arrangements for the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve in accordance with the nationally agreed framework for applying the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development to fisheries.

The MIFRMP describes:

- The geography of Mallacoota Inlet; available information on recreational fishing activities; and other values/uses of the inlet and surrounds that may affect recreational fishing opportunities;

- Current management arrangements for fishing activities and for other relevant values/uses of the inlet and surrounds;

- Goals, objectives, performance indicators and actions for management of fishing activities in the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve; and

- Processes for participating in management of other relevant values/uses in and around the inlet, to ensure any possible concerns regarding consequences for recreational fishing can be raised and considered.

Available evidence from fishery monitoring and assessment programs indicate that current levels of fishing in Mallacoota Inlet are sustainable and, therefore, existing fishery management arrangements will initially remain unchanged. New or expanded programs will be established to monitor recreational fishing activities, to assess the status of the two key recreational fishing target species - dusky flathead and black bream, and to identify key fish habitats in the inlet.

If information obtained from these programs indicates a need to alter fishery management arrangements in the future, to ensure sustainable use or to meet changing demands for recreational fishing opportunities, then changes will be considered in consultation with stakeholders.

Priorities for implementation and indicative costs of the actions identified in the MIFRMP are provided. Annual progress reports and a 10 year review process will allow fishery management arrangements for the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve to be adapted to changing circumstances, ensuring sustainable use of fisheries resources with enhanced economic and social benefits to the community.

A reference group will be established to work with the Department of Primary Industries to deliver the key management outcomes from the MIFRMP.

Introduction

On 22 January 2004, Mallacoota Inlet was declared a fisheries reserve under the provisions of Section 88 of the Fisheries Act 1995. The defined area of the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve is Mallacoota Inlet, including the Top Lake, Bottom Lake, The Narrows and estuarine sections of the inflowing Wallagaraugh River below the Victorian/New South Wales border and the Genoa River below the junction with the Maramingo River. The fisheries reserve does not include Goodwin Sands or any other area forming part of the Croajingolong National Park. A notice published in the Victorian Government Gazette (see Appendix 1) indicates that the purposes of the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve are to:

- Provide for enhanced recreational fishing opportunities;

- Improve the management and monitoring of recreational fishing activities;

- Improve the management and monitoring of any other issues that are likely to have an impact on recreational fishing opportunities; and

- Enable the development of a management plan that provides for appropriate control of fishing activities and equipment, and provides a strategy for ensuring compliance with these controls.

The Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve Management Plan (MIFRMP) specifies the objectives, strategies and performance measures for managing fishing activities within the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve, and was developed in consultation with recreational fishers and other interested sectors of the community. The MIFRMP formalises fishery management arrangements for the next 10 years in accordance with the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development (Fletcher et al. , 2002).

The MIFRMP also describes other uses, activities and environmental processes in and around Mallacoota Inlet that may influence fishing opportunities or the productivity of fish habitats in the inlet. The MIFRMP identifies agency responsibilities and processes for management of these non-fishing uses/activities, and actions needed to ensure that any concerns regarding possible consequences for fishing or fish habitat can be raised and considered in the appropriate forums.

Description of Mallacoota Inlet and its catchment

Mallacoota Inlet is the eastern-most estuary in Victoria and is located about 550km east of Melbourne and is approximately 25 sq km in size (Hall et al. , 1985; MacDonald et al. , 1997).

Mallacoota Inlet is surrounded by approximately 86,000 hectares of both public and private land. The Croajingolong National Park surrounds the majority of the inlet while state forest, the townships of Mallacoota and Gipsy Point and several other private properties occupy small tracts of foreshore land (LCC, 1993; MacDonald et al. , 1997).

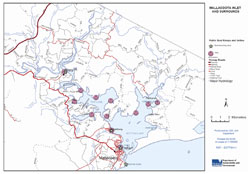

Mallacoota Inlet contains two lagoons or lakes locally known as the Top Lake and the Bottom Lake (Figure 1). The two lakes are linked by a deep channel which is locally known as "The Narrows." Mallacoota Inlet's biggest tributaries are the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers with their catchments extending into NSW. Both rivers have been subject to increased sediment loadings as a result of stream-side vegetation clearing (particularly around the township of Genoa), forestry practices and inappropriate land management practices in the catchment (Erskine, 1992; MacDonald et al. , 1997; DPI, 1999). Other smaller tributaries that run into Mallacoota Inlet include the Maramingo River, Little River, Harrison Creek, Coolwater Creek and Dowell Creek.

Saltwater of marine origin is found in both Lakes and has been known to extend considerable distances up the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers during low water flow periods (MacDonald et al. , 1997).

MacDonald et al. (1997) have suggested that the physical nature of the Bottom Lake is determined by sedimentary processes derived from three main sources:

- deposition of alluvial sediments from rivers and streams;

- introduction of marine sands by flood tides; and

- run off from the adjacent banks of the inlet.

Fresh water that travels downstream from the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers to the Bottom Lake carries mainly fine silty sediments, while tidal flows of oceanic marine water carry coarser marine sands into the Bottom Lake.

Such movements of sand have resulted in a tidal delta adjacent to the entrance of the inlet which is one of Victoria's largest (McRae-Williams et al. , 1981). Another major feature in the northern part of the Bottom Lake is the Goodwin Sands, which was originally part of a coastal barrier between the inlet and the sea at a time when sea levels were much lower. Over time, Goodwin Sands has eroded resulting in a series of small islands, sand banks and spits (Williams, 1980). Goodwin Sands is now home to a large number of internationally, nationally, regionally and locally significant migratory birds.

The Top Lake was formed when the lower Genoa and Wallagaraugh river valleys were drowned at the end of the last Ice Age, and sediments in this lake are dominated by deposits from rivers and streams.

The inlet is usually open to the ocean all year round through a shallow entrance (up to 2.5 m in depth), however the entrance is known to be closed during periods of low runoff. The configuration of the entrance channel may change frequently as a result of fluctuations in freshwater inflows to the inlet and from oceanic conditions such as tidal and storm surges (MacDonald et al. , 1997).

The waters of the Bottom Lake are usually marine except when flooding of the Wallagaraugh or Genoa rivers occurs following heavy rainfall. Such events may lead to temporary salinity stratification in the Bottom Lake and elevated nutrient loads. The salinity characteristics of the Top Lake are much more variable depending on freshwater inflows from the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers.

The annual rainfall in the area is between 900 and 1,000 mm with historical data indicating that rainfall is spread evenly throughout the year (MacDonald et al. , 1997).

Annual fluctuations in salinity, water temperature, water quality, habitat, food availability and condition of the inlet entrance are likely to influence breeding success, survival of larvae and small juveniles, growth rates and rates of immigration/emigration from the estuary (MacDonald et al. , 1997; DPI, 2001).

Declaration of Mallacoota Inlet as a fisheries reserve

Prior to the November 2002 State election, the Victorian Government indicated its commitment to improving recreational fishing opportunities by proposing the establishment of fisheries reserves in three Gippsland estuaries: Anderson Inlet, Mallacoota Inlet and Lake Tyers. The proposals for Lake Tyers and Mallacoota Inlet included the removal of commercial fishing other than fishing for eels and bait.

Public submissions received between October and December 2002 indicated support for these proposals. Mallacoota Inlet was gazetted as a fisheries reserve on 22 January 2004, primarily for the purposes of maintaining or enhancing recreational fishing opportunities.

Recreational fishing

Results of the recent National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey (Henry and Lyle, 2003) indicate that approximately 550,000 Victorians or 13% of the State's population, went recreational fishing in the 12-month period prior to May 2000. Approximately 43% of total Victorian recreational fishing events in 2000/01 occurred in bays, inlets and estuaries, including Mallacoota Inlet. The majority of this effort was probably expended in the larger bays and estuaries such as Port Phillip Bay, Western Port and the Gippsland Lakes.

The National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey (NRIFS) also found that Victorians spent approximately $400 million on goods and services associated with recreational fishing activities during 2000/01. This was equivalent to $721 per fisher per year – the highest per capita expenditure in Australia. Approximately two thirds of this expenditure occurred in the Melbourne metropolitan area, but it is nevertheless clear that recreational fishing can significantly contribute to local or regional economies.

Further analysis of Victorian data from the NRIFS has indicated that bream (mostly black bream but also some silver bream) and dusky flathead were the two largest components of the estimated total recreational fishing catch from Mallacoota Inlet in 2000/01. The NRIFS results also indicated that the estimated annual dusky flathead catch from Mallacoota Inlet was the largest of any Victorian inlet or estuary.

Profile of recreational fishing in Mallacoota Inlet

Most recreational fishing in Mallacoota Inlet is angling. Peak recreational fishing seasons occur in January, April and September and coincide with public and or school holiday periods (MacDonald et al. , 1997). Hall et al. (1985) identified, through an examination of the distribution of angling effort by area and time, that between December and April in any given year, the Bottom Lake experienced the most angling pressure by boatbased fishers. Angling pressure by boat-based fishers was found to increase in the Top Lake and inflowing rivers between the months of June and October with black bream being the main recreational target species (Hall et al. , 1985). Recreational prawning is also very popular with residents and visitors in the Bottom Lake in late summer and early autumn.

Boat-based fishing in Mallacoota Inlet is predominantly from small powered boats (up to six metres) that are usually launched from boat ramps located at the Mallacoota township, Gipsy Point or Karbeethong.

Shore-based fishing is restricted to a small number of locations (particularly jetties/landings and unvegetated foreshores) around the Bottom and Top Lakes and in some reaches of the Wallagaraugh River.

Key fish species

Information collected during public consultation processes for this management plan suggests that in recent years, the main target species for recreational fishers in Mallacoota Inlet are black bream and dusky flathead.

An extensive boat-based recreational fishing creel survey undertaken from 1981 to 1984 (Hall et al. , 1985) indicates that, in addition to bream and dusky flathead, smaller numbers of anglers were targeting a range of other species, including tailor, mulloway, luderick, King George whiting, garfish, Australian salmon and trevally. Other species that are caught in the inlet or have been targeted in the past include prawns, sand whiting and yellow-eye mullet. All target species are either permanent estuarine residents or rely on estuaries as nursery habitats (MacDonald et al. , 1997).

Fishing catch and effort

The only information on annual recreational fishing catch and effort within Mallacoota Inlet comes from a creel survey undertaken between December 1981 and June 1984 (Hall et al. , 1985) and from preliminary analyses of Victorian data from the 2000/01 NRIFS.

Hall et al. (1985) estimated that the mean angling effort to be 154,000 hours or 30,000 angler days. The estimated annual retained recreational catch was 48,000 fish with an estimated weight of almost 27 tonnes.

The main components of the recreational catch were black bream and dusky flathead, with smaller catches of trevally, tailor and snapper. Comparisons between the recreational and commercial harvest between 1981 and 1984 show that recreational anglers accounted for 36% of the total Mallacoota Inlet catches. Recreational anglers accounted for 44% of total bream catches, 93% of total dusky flathead catches, 27% of all tailor, 20% of all trevally and less than 5% of all luderick (Hall et al. , 1985; NREC, 1991).

Preliminary analysis of 2000/01 NRIFS data indicates that the estimated total annual retained catch of bream from Mallacoota Inlet was about 17,500 fish which represented about 40% of the total retained bream catch from the inlet that year. The estimated 2000/01 recreational retained catch of dusky flathead was about 73,000 fish which represented more than 95% of the total retained flathead catch from the inlet that year.

Commercial fishing

Commercial fishing has a long history within Mallacoota Inlet. The industry commenced in the 1880s and closed in 2003 when the remaining four Mallacoota Inlet Fishery Access Licences were cancelled. There is currently one fishing licence that permits eel fishing and several licences that allow for commercial bait fishing in Mallacoota Inlet.

The main target species for commercial bait collection are prawn and bass yabbies.

Recording of commercial fishing activities (total commercial catch by species) within Mallacoota Inlet began in 1916 and ceased in 2003.

Estuary and garfish seine nets were commonly used within the lower lake of Mallacoota Inlet. Annual commercial catches have varied considerably with a maximum of 220 tonnes recorded in 1953 and a minimum of 24 tonnes in 1966/67. Most catches since 1978/1979 were above 50 tonnes (DPI, 2001). Black bream and luderick were the main target species although significant catches of river garfish, Australian salmon, trevally, yellow-eye mullet, yellowfin bream and dusky flathead were also taken (NREC, 1991; MacDonald et al. , 1997).

Estimated wholesale market value of the annual commercial catch more than doubled from about $85,000 in the late 1970s to more than $200,000 in the last few years of the fishery (MacDonald et al. , 1997; Anon., 2001). Table 1 summarises the mean annual commercial finfish catches from Mallacoota Inlet between 1978 and 2003.

Table 1. Annual commercial fish catches (kg) from Mallacoota Inlet during 1978 – 2003

| Species | Highest Annual Catch | Lowest Annual Catch | Mean Annual Catch | % of Total Catch for the Period 1978-2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All species total | 118209 | 26093 | 72220 | 100 |

| Australian salmon | 40451 | 15 | 8485 | 12.4% |

| Bream, black | 31554 | 1264 | 13014 | 19A |

| Bream, yellowfin* | 4649 | 33 | 318 | 0.50% |

| Flathead, dusky (incl. small catches of sand & yank flathead) | 2939 | 206 | 1202 | 1.A |

| Garfish, all species | 11408 | 58 | 2885 | 4.20% |

| Leatherjacket | 2636 | 12 | 396 | 0.A |

| Luderick | 31014 | 1224 | 16318 | 23A |

| Mullet, sea | 12748 | 390 | 5213 | 7.60% |

| Mullet, yellow-eye, sand and flat-tail | 12684 | 1257 | 4278 | 6.A |

| Mulloway | 1102 | 29 | 310 | 0.A |

| Perch, estuary | 275 | 24 | 87 | 0.A |

| Prawn, all species | 4474 | 58 | 888 | 1.30% |

| Snapper | 444 | 2 | 75 | 0.A |

| Tailor | 15198 | 490 | 6028 | 8.A |

| Trevally | 16109 | 771 | 6757 | 9.A |

| Whiting, King George | 3539 | 4 | 652 | 1.00% |

| Whiting, sand | 2879 | 23 | 694 | 0.78% |

| Whiting, unspecified | 7182 | 42 | 1345 | 2.00% |

* Prior to 1995, species was not distinguished from black bream

Biology and ecological requirements of key target recreational fish species

The following descriptions of the biological and ecological characteristics of key target recreational fish species in Mallacoota Inlet are derived from published literature. While some recreational fishers have extensive knowledge of the distribution and behaviour of key fish species in Mallacoota Inlet based on personal observations, there has been little or no scientific investigation of the distribution, population dynamics or ecological requirements of fish species in the inlet. The list of species for the MIFRMP has been identified from the public consultation process and anecdotal evidence and is not considered to be a definitive list of key target species. Further information on species other than black bream, dusky flathead, silver trevally, yellowfin bream and Australian salmon can be found in Appendix 2.

Black bream

Black bream (Acanthopagrus butcheri) is an endemic species which inhabit estuarine waters of southern Australia to Western Australia with the range often found to overlap with yellowfin bream (Acanthopagrus australis) (Kailola et al., 1993). These two species are morphologically very similar and are said to hybridise in some areas where they coexist (Rowland, 1984).

Bream is a demersal species and may be found inhabiting rocky river beds, structures (e.g. jetties) and snags, and may be caught over seagrass beds, mud and sand substrates (Kailola et al., 1993; Cashmore et al., 2000). Black bream are rarely found at sea, although some adult bream may migrate between estuaries (Hall, 1984).

Larvae and small juvenile black bream are found primarily amongst seagrass beds which provide ideal habitat conditions including the availability of small invertebrate prey and adequate shelter for the species (Kailola et al., 1993; Cashmore et al., 2000).

Spawning for this species usually occurs from August in any given year; however it may begin later in more westerly estuaries (Cadwallader and Backhouse, 1983). Within the Gippsland Lakes, bream have been found to spawn from October to early December and in Mallacoota Inlet, black bream are thought to migrate upstream to the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers during spring (Hall et al., 1985). Anecdotal evidence from local fishers familiar with the inlet suggests that spawning occurs in deeper water with muddy bottoms as the deeper water is thought to provide protection (DPI,1999).

The survival of black bream larvae appears to be heavily dependent on suitable salinity and water temperature conditions as well as food and habitat availability (Kailola et al., 1993; Cashmore et al., 2000).

Female black bream first spawn at approximately 24 cm in length and can release between 300,000 and 3 million eggs depending on environmental conditions. Males become sexually mature at 22 cm (Butcher, 1945; Hall, 1984; Kailola et al., 1993).

Anecdotal evidence suggests that juvenile black bream in Mallacoota Inlet are mostly found in the Top Lake where the species lives in vegetated areas, with larger juveniles found in the Bottom Lake (DPI, 1999).

Black bream feed primarily on polychaetes with bivalves and amphipods considered a secondary component of their diet (Cashmore et al., 2000). Recreational fishers participating in the Mallacoota Inlet Fishery Assessment workshop in February 2006 reported observations of black bream closely associated with beds of small mussels in shallow water, suggesting that this is a significant source of food in Mallacoota Inlet (DPI, 2006a). Adult black bream are considered to be opportunistic feeders on a wide variety of prey including bivalve and gastropod molluscs, prawns and crabs, polychaete worms and small demersal fish (Rigby, 1982; Kailola et al. 1993; Cashmore et al., 2000).

Anecdotal evidence obtained from fishers participating in the Mallacoota Inlet Fish Habitat Assessment workshop in 1999 suggested that at the time, good catches of black bream occurred upstream of Gipsy Point and in the Wallagaraugh and Genoa rivers in the winter months (DPI, 1999).

Dusky flathead

Dusky flathead (Platycephalus fuscus) are an endemic species to Australia and are found in bays, estuaries and inshore coastal areas from Cairns in Queensland to the Gippsland Lakes in Victoria (Kailola et al., 1993).

Dusky flathead may be found residing over mud, silt, sand and gravel beds as well as seagrass beds (predominantly Zostera spp.) (Kailola et al., 1993). Anecdotal evidence from anglers presented at a Fish Habitat Assessment workshop in 1999 (DPI, 1999) suggests that in Mallacoota Inlet, dusky flathead use different parts of the estuary at different times of the year.

Dusky flathead are thought to spawn in response to water temperature and, therefore, the warmer months of January to March appear to suit the species spawning requirements. However, there are no published data on the frequency of spawning and fecundity (Kailola et al., 1993). Dusky flathead are thought to spawn from January to March in NSW and Victorian waters (Kailola et al., 1993). Anecdotal observations suggest that in Mallacoota Inlet, possible spawning grounds may be in the Bottom Lake around Harrisons Channel and sandbank areas from January to March (DPI, 1999; 2006b). However, it is possible that dusky flathead spawned in open coastal waters, or in estuaries up the east coast of Australia, may also be a source of juvenile recruitment to Mallacoota Inlet.

It has been found that dusky flathead are larger in size at the time of maturity in warmer waters compared with cooler waters (Kailola et al., 1993). Dusky flathead are ambush predators with prey including other fish (mullet or whiting), crabs, prawns, other crustaceans and polychaete worms (Kailola et al., 1993).

Kailola et al. (1993) suggests that it is possible for dusky flathead populations to be affected by loss of seagrass, sedimentation and changes in habitat and environment, particularly along east coast estuaries and inlets.

Anecdotal evidence and information collected from the public submission process for the preparation of this plan, suggests that dusky flathead are caught all year round. Higher levels of angling occur in the summer months throughout the inlet.

Yellowfin bream

Gomon et al. (1994) reports that yellowfin bream are endemic to the waters of eastern Australia, with a range from northern Queensland to the Gippsland Lakes.

Yellowfin bream reach maturity at three to four years of age (or about 24 cm in length) (Anon, 1981) and are thought to live up to 20 years of age (Henry, 1983). Individuals may change sex (male to female) after the first breeding season (Anon, 1981).

Pollock (1982) indicates that species found in Queensland generally spawn between late autumn to winter, with spawning taking place near the mouths of estuaries or in surf zones. Evidence presented by participants at the Mallacoota Inlet Fish Habitat Assessment workshop in 1999 indicates that the species may spawn up to 400-500 metres either side of the entrance (DPI, 1999).

Yellowfin bream eggs are thought to drift to sea and hatch approximately two to three days after fertilisation, with larvae developing in coastal waters (DPI, 1999). Pollock et al. (1983) reports that after about one month, post-larvae enter estuaries where they utilise plankton until they are about 13 mm in length. Zostera spp. and other shallow macrophyte beds are thought to be an important nursery habitat for juvenile yellowfin bream (West and King, 1996).

It appears that yellowfin bream use similar habitats to black bream, although the species is not constrained to estuaries and other brackish waters (Anon, 1981).

Yellowfin bream feed on a large range of organisms including crabs, prawns, shrimp, polychaete worms, molluscs and other small fish (Anon, 1981).

Silver trevally

Trevally species of the genus Pseudocaranx are widespread in temperate and sub-tropical waters of Australia, New Zealand, the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean (James, 1984). In Australia what was thought to be a single species, P. dentex, occurs from about Rockhampton in central Queensland around all southern states (including Tasmania) to North West Cape in Western Australia (Kailola et al., 1993).

Studies in the early 1990s have revealed that silver trevally in Victorian, Tasmanian, South Australian and Western Australian waters consist of two very similar species, P. dentex and P. wrighti (Gomon et al. 1994).

Juvenile silver trevally occur over soft substrates in estuaries, bays and shallow coastal waters, whilst adults are found either in shallow coastal waters or forming pelagic schools in deeper waters off the continental shelf (Last et al., 1983; James, 1976).

Spawning occurs during summer (Lenanton, 1977). Adult fish in spawning condition have been recorded from both estuaries and offshore areas (Winstanley, 1985), but spawning habitat preferences have not been identified. Anecdotal evidence from anglers attending the Mallacoota Inlet Fish Habitat Assessment workshop suggests that adults migrate into the inlet over the summer months where they are found residing in seagrass beds (DPI, 1999). Good catches of the species in Mallacoota Inlet have been observed through the winter months with adult species thought to leave the inlet at the end of winter (DPI, 1999).

Silver trevally can live for more than 40 years (James, 1978), and have been reported to grow to a total length up to 94 cm (Hutchins & Swainston, 1986) and up to 6 kg in weight (Last et al., 1983). However, trevally larger than about 38 cm length are uncommon in Victorian bays, estuaries and shallow coastal waters.

Silver trevally are opportunistic carnivores, adapted to both benthic and planktonic feeding modes. The benthic diet consists of polychaete worms, molluscs and small crustaceans, while surface schools of trevally consume planktonic crustaceans - particularly euphausids (krill). Juvenile trevally mainly consume micro crustaceans (Winstanley, 1985). Seasonal feeding preferences occur in adult trevally with a summer diet of essentially crustaceans shifting to mainly bivalve molluscs and fishes in winter (Anon., 1981).

Australian salmon

Australian salmon are migratory, schooling marine fishes found in coastal waters, bays and estuaries of southern Australia and up the east and west coasts to approximately 30°S (Kailola et al., 1993).

Morphological and genetic studies (MacDonald, 1980; 1983) have confirmed two species of salmon in southern Australian waters: western salmon (Arripis truttaceus) in waters of Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania; and eastern salmon (A. trutta) in waters of southern NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.

Eastern salmon predominate in East Gippsland waters and are relatively common as far west as Port Phillip Bay. Eastern salmon spawn in coastal waters of East Gippsland and southern NSW over the period November to April.

In Victoria, both western and eastern salmon up to 2+ years are found predominantly in bays and estuaries, often in association with seagrass beds. They can tolerate temperature and salinity extremes such as the brackish and turbid waters of estuaries, or the hyper-saline waters of the South Australian gulfs.

Eastern juveniles feed on zooplankton but are known to also prey on bottom-dwelling fauna such as fishes, squid, crustaceans and polychaete worms during winter months (Robertson, 1982).

Larger juvenile salmon (>30 cm length) move out of bays and estuaries into more exposed coastal waters, such as around rocky headlands and along surf beaches. Maturing salmon school up and move east or west along the southern coast to the respective spawning grounds of each species.

Migrating schools of adult salmon will sometimes 'rest up' near the mouths of inlets such as Mallacoota Inlet, and may occasionally move into such inlets to feed.

Significance of Mallacoota Inlet to Traditional Owners

Prior to European settlement, the far east Gippsland region was part of the Country of the Bidwell (Bidawal) Clan whose people occupied the coast between Green Cape NSW and Cape Everard (Point Hicks), inland to Delegate NSW and on the headwaters of the Cann and Bemm Rivers (Laughton, pers. comm.). The community/Traditional Owners were productive hunters and fishers who spent most of their time along the coastline, rivers and estuaries where fresh water and a diverse range of food was plentiful. Larger estuaries like Mallacoota Inlet were probably the richest food resource areas (Coutts, 1981). The Bidawal people also occupied Gabo Island for their ceremonies.

Mallacoota Inlet and surrounding country is still used by and has great cultural significance for aboriginal people/Traditional Owners based on traditions - including landscape and seascape values - descended from the original Indigenous custodians of Country in this area.

Sites of cultural significance

Mallacoota Inlet and surrounds (including Croajingolong National Park) contain areas of high significance including archaeological sites, middens, scarred trees, burial sites and scatters of stone artefacts (DNRE, 1996; AAV, 2002; EGCMA, 2005). Many of these sites have been listed on the Register of the National Estate. Other sites are of spiritual importance. Souvenir hunting, erosion and inappropriate recreation (including unauthorised access) have been identified as the main threats to these significant sites (DNRE, 1996). All sites of cultural significance and artefacts are protected by both State and Commonwealth legislation. Aboriginal Affairs Victoria (AAV) is the responsible authority for the administration of the relevant Acts. Enquiries in relation to registered or noted sites of significance should be directed to AAV. Any proposed works or use of Crown land are required to be carried out in accordance with the 'future acts' provision of the Native Title Act 1993, the Aboriginal and Archaeological Relics Preservation Act 1992 and part IIA of the Commonwealth Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984.

Information regarding Indigenous fishing activities can be found under the 'Current Management Arrangements' section of the MIFRMP. Information pertaining to current controls on fishing by Indigenous Australians can also be found under the 'Current Management Arrangements' section.

Other uses of Mallacoota Inlet

Mallacoota Inlet is widely used by residents as well as visitors in peak holiday periods, not only for its recreational fishing activities, but also for the isolation and scenic attractions that the surrounding Croajingolong National Park (CNP) has to offer (Hall et al., 1985). The main attractions of the area are water and shore-based recreational activities, including bushwalking and wildlife observation within the adjoining CNP.

The main water-based activities undertaken in and around the inlet are beach combing, swimming, fishing, site seeing and wildlife observation.

Water-based activities

A large number of watercraft users enjoy the many opportunities the inlet has to offer including recreational boating, wind surfing, canoeing, kayaking, sailing, water-skiing, and personal watercraft use. Boat hire businesses are located at several points around the inlet, including Mallacoota, Karbeethong and Gipsy Point. There is at least one fishing charter operation in the inlet. Canoeing and kayaking are popular activities that occur throughout the inlet when weather and tidal conditions are suitable.

Water-skiing and personal watercraft usage are popular throughout the Top Lake and Bottom Lake, particularly at Cemetery Bight, the Narrows, Dead Finish, Cape Horn and Double Creek Arm, where water depths and shelter are conducive to such activities.

Nature tours also operate through peak seasons within the inlet.

While the inlet supports a variety of watercraft activities, increasing demand for these activities, particularly during peak holiday periods may lead to congestion both on the water and at boat launching access points.

Watercraft can be launched from a number of locations including Mallacoota, Karbeethong, Bucklands Jetty and Gipsy Point. The boat ramps at Karbeethong and Mallacoota are the most popular and in peak times may become congested.

There are a large number of public use jetties around the inlet where watercraft users can moor their vessels and enjoy public facilities particularly in the CNP area. Overnight stays are prohibited within the boundaries of the CNP adjacent to the inlet.

Commercial boat berthing opportunities are available near the Mallacoota township.

Shore-based activities

Major shore-based activities as identified by Hall et al. (1985), DNRE (1996) and EGSC (2001) include picnicking, photography, nature appreciation, camping, walking, bicycle riding, horse riding, site seeing and orienteering. Some activities may be restricted due to limited shore access or management constraints, particularly activities within the CNP.

Intensive use of some of the shore locations, particularly around the townships of Mallacoota, Karbeethong and Gipsy Point, has resulted in environmental degradation including the removal of indigenous vegetation, uncontrolled vehicle and pedestrian access, pest plant and animal establishment, and extension of private residential backyards onto foreshore Crown land (EGSC, 2001).

Current management arrangements

Following the removal of commercial fishing (other than for eels and bait) from Mallacoota Inlet in April 2003, and the declaration of the inlet as a fisheries reserve in January 2004, the focus for fisheries management has shifted towards maintaining and, where possible, improving recreational fishing opportunities in Mallacoota Inlet.

The following sections describe the policy framework, legislative tools, management processes and current controls that apply to recreational fishing in Mallacoota Inlet and other Victorian waters.

Legislative and policy framework for fisheries management

Legislation

Fishing activities in Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve and in all Victorian public waters are managed under the provisions of the Fisheries Act 1995 (the Act) and the Fisheries Regulations 1998 (the Regulations).

The Act provides a legislative framework for the regulation and management of Victorian fisheries and for the conservation of fisheries resources, including their supporting aquatic habitats. The stated objectives of the Act are:

- to provide for the management, development and use of Victoria's fisheries, aquaculture industries and associated aquatic biological resources in an efficient, effective and ecologically sustainable manner;

- to protect and conserve fisheries resources, habitats and ecosystems including the maintenance of aquatic ecological processes and genetic diversity;

- to promote sustainable commercial fishing and viable aquaculture industries and quality recreational fishing opportunities for the benefit of present and future generations;

- to facilitate access to fisheries resources for commercial, recreational, traditional and nonconsumptive uses; and

- to encourage the participation of resource users and the community in fisheries management.

The Act also provides for the development, implementation and review of fisheries reserve management plans, facilitates participation of stakeholders in fisheries management via fisheries co-management arrangements, and prescribes enforcement powers to assist in achieving compliance with fishing controls.

The Regulations prescribe detailed management arrangements for individual commercial and recreational fisheries, including licence requirements, restrictions on fishing equipment and methods, restrictions on fishing catch and or effort (bag limits, size limits, closed seasons/areas), and penalties for breaches of fishing controls.

It is important to note that the provisions of fisheries legislation (including Fisheries Notices) can only be applied to the control of fishing activities. Other human activities (e.g. catchment land use, foreshore development and other waterbased recreational activities) that may directly or indirectly affect fish habitats, fishery resources or the quality of fishing, are managed by different agencies under a variety of other legislation.

Policy

All Australian governments, including Victoria, have made a commitment to manage fisheries according to the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development (ESD). These principles include:

- ensuring that fishing is carried out in a biologically and ecologically sustainable manner;

- ensuring that there is equity within and between generations regarding the use of fish resources;

- maximising economic and social benefits to the community from fisheries within the constraints of sustainable utilisation;

- adopting a precautionary approach to management – particularly for fisheries with limited data; and

- ensuring that the processes and procedures involved in management of a fishery are appropriate, transparent and inclusive.

There is an expectation in Australia and worldwide that utilisation of fish resources will be managed according to ESD principles, and they have been followed during the development of the MIFRMP.

Indigenous fishing activities

The provisions of the Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993 apply to all types of management of Mallacoota Inlet.

An application for a native title determination which covers parts of East Gippsland including Mallacoota Inlet, was lodged with Federal Court by the Bidwell People in 2002, but has since been discontinued.

In November 2000, the Victorian Government signed a Native Title Protocol with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and the native title representative body, Native Title Services Victoria. The protocol required the development of a statewide policy framework to address a broad range of native title related issues, including fisheries.

Initial discussions with stakeholder groups have been held to identify fisheries issues relating to native title.

The Victorian Government is currently working with Indigenous community representatives, Australian fisheries authorities and other fishing stakeholders to develop a national set of principles and pathways to facilitate definition and lasting recognition of customary fishing practices; increased opportunities for economic engagement of Indigenous communities in fisheries-related enterprises; and increased Indigenous participation in all aspects of fisheries use and management.

Current controls on fishing

Recreational fishing licence

A Recreational Fishing Licence (RFL) is required for angling, bait pumping, hand collecting and all other forms of recreational fishing in Victorian public waters, including Mallacoota Inlet. Some sectors of the community, including people under 18 or over 70 years of age, holders of a Victorian Seniors Card, and recipients of various age, disability or veterans benefits, are exempt from the need to hold this licence to go fishing.

Recreational fishing equipment

The Regulations define "recreational fishing equipment" as including a rod and line, handline, dip/landing net, bait trap, spear gun, hand-held spear, bait pump, recreational bait net and recreational hoop net. Recreational use of any equipment not included in this definition is prohibited in all Victorian public waters. The maximum permitted dimensions of dip nets, bait traps, bait pumps, recreational bait nets and recreational hoop nets are prescribed in the Regulations and summarised in the Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide.

Inland and marine waters

The Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve contains both marine and inland waters. The Bottom Lake has been classified as marine waters whereas The Narrows, Top Lake and waters upstream of Gipsy Point are classified as inland waters for the purposes of the Act.

Restrictions on use or possession of recreational fishing equipment in Victorian inland and marine waters are prescribed in the Regulations and summarised in the Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide. Most notably, anglers are currently restricted to using no more than two lines each in inland waters and no more than four in waters classified as marine. The possession and use of a speargun in Mallacoota Inlet is also prohibited.

Size and catch limits

Legal minimum sizes, bag limits, possession limits (in, on or next to fishing waters) and vehicle limits for fin fish and invertebrate species that may be encountered by recreational fishers in Mallacoota Inlet, are prescribed in the Regulations or current Fisheries Notices, and are summarised in the Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide.

Some size and catch limits have been introduced as measures to protect fish stocks from unsustainable fishing pressure. However, many of these limits have been adopted on ethical or cultural grounds, such as defining a reasonable take for personal consumption.

Since December 2003, recreational fishing for dusky flathead in Mallacoota Inlet and other Victorian waters has been subject to interim stricter catch limits, introduced by Fisheries Notice, to protect dusky flathead from increased targeting by anglers using increasingly sophisticated recreational fishing techniques.

Requirement to land fish in whole or carcass form

For some fish species with high commercial market value and which are subject to size limits, there is a requirement to retain captured fish in whole or carcass form until after they have been landed (brought ashore), in order to ensure compliance with recreational size and catch limits. Marine or estuarine fish species required to be landed in whole or carcass form include all shark species, elephant fish, King George whiting, bream, snapper and eels. In the case of sharks and elephant fish, 'carcass' means a fish which has been gutted and headed forward of the first gill slit, but has not been skinned or filleted. In the case of scale fish, 'carcass' means a fish which has been scaled and gutted, but has not been headed or filleted.

Intertidal collection of shellfish

Controls on intertidal collection of shellfish and other invertebrate animals are prescribed in the Regulations and are summarised in the Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide.

Currently, shellfish and other invertebrate animals may be collected by hand or using an approved bait pump from most Victorian intertidal waters, including Mallacoota Inlet. The use of a scoop, dredge, fork, spade, rake, shovel or other digging implement to collect invertebrate species from the intertidal zone throughout Victoria is prohibited.

Fishing by Indigenous Australians

The only types of fishing activities currently defined under the provisions of the Act and the Regulations are commercial fishing, recreational fishing and aquaculture. Access to Victorian waters for each of these types of fishing requires a licence or permit (although some categories of recreational fishers are exempt from this requirement), and is subject to a range of licence conditions and or regulations.

Customary fishing practices by Indigenous Australians are not identified as a distinct type of fishing activity under current Victorian legislation, and non-commercial fishing by Indigenous Australians is therefore treated as recreational fishing.

The Act does provide for the issue of permits to facilitate the taking of fish and other species for specified Indigenous cultural ceremonies or events.

Fishery co-management arrangements

Co-management is an inclusive arrangement that brings industry, community and government together to participate in the management of a natural resource. It assists those involved by improving their collective understanding of individual stakeholder needs and aspirations and by identifying behavioural modifications that can increase the long term viability of the resource – and therefore continued access to that resource by user groups.

The co-management of fisheries within Victoria is a process involving three entities. The first comprises the peak bodies, including VRFish and Seafood Industry Victoria.

The second entity comprises the Fisheries Comanagement Council (FCC) and its expertise based committees.

Finally, the third entity is the government agencies, including the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) of which Fisheries Victoria is a division.

The above co-management entities seek to ensure that fisheries interests are appropriately acknowledged and represented during consultation processes regarding decisions that may have an impact on any given fishery.

Management of non-fisheries uses/values in and around Mallacoota Inlet

Wildlife and native vegetation protection

Mallacoota Inlet and its shores contain a variety of aquatic and terrestrial habitats that support a diverse array of plant and animal species and communities, some of which may be protected under Commonwealth (e.g. Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999) and or State legislation (e.g. Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988).

All islands, sandflats, shoreline vegetation and mudflats (particularly Goodwin Sands) exposed in the Bottom Lake at low tide provide fauna, particularly migratory wading birds and shorebirds, with ideal feeding grounds and habitat (DNRE, 1996).

Noted rare or threatened aquatic species reported to occur in Mallacoota Inlet include the Cox's gudgeon, freshwater herring, Australian grayling and the Mallacoota burrowing crayfish (DNRE, 1996; EGSC, 2001). These species have been listed as threatened under Schedule 3 of the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 and as a result, Action Statements are required specifying measures to protect these species. Implementation of Action Statements is the primary responsibility of the Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE), with input from other stakeholders.

Coastal salt marsh and seagrass communities occur in parts of Mallacoota Inlet and are thought to provide important habitat, feeding and nursery grounds for a range of aquatic biota, including fish species.

Seagrass coverage in Mallacoota Inlet is approximately 6.5 km² (or 22% of the inlet area) with Zostera spp. being the most widely distributed species and Ruppia spp. also being observed in various locations (Blake et al., 2000).

The CNP surrounds much of Mallacoota Inlet and is managed by Parks Victoria. The CNP along with Nadgee Nature Reserve in NSW forms part of the Croajingolong National Park Biosphere Reserve designated under the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Man and the Biosphere Program (DNRE, 1996).

Key objectives and strategies for protection of biodiversity areas around Mallacoota Inlet are described in the Victorian Biodiversity Strategy (DNRE, 1997), the Mallacoota Foreshore Management Plan (EGSC, 2001) and in sections of the Croajingolong National Park Management Plan (DNRE, 1996).

Management of foreshore access and facilities

The Mallacoota foreshore, particularly between the Mallacoota township and Devlins Inlet, is a focal point for boat launching, cruises, sightseeing, walking, cycling, camping, fishing, horse riding and swimming.

Shore-based recreational activities tend to be concentrated around boating access points such as Mallacoota, Karbeethong and Gipsy Point. Public jetties are located around the inlet providing good access for picnicking and BBQ facilities and some walking tracks.

Parks Victoria manages a number of picnic facilities and jetties surrounding the inlet within the CNP. The park provides vehicle, vessel or walker access to these areas in accordance with the Croajingolong National Park Management Plan (DNRE, 1996).

Cape Horn Track, Genoa River Fire Trail, Souwest Arm Track and Sandy Point Track are all open to the public and provide vehicle, vessel and or pedestrian access to the Top Lake and Genoa River. Access to Goanna Bay, Gravelly Point, Captain Creek and The Narrows is by foot or vessel. Track maintenance is undertaken by Parks Victoria in accordance with the specifications of the Croajingolong National Park Management Plan (DNRE, 1996).

Strategic directions identified in the Victorian Coastal Strategy (VCC, 2002) include the requirement that public access to coastal Crown land will be maintained except where the interests of security, safety or protection of coastal resources predominate. The Strategy also specifies that public access to existing shore-based fishing facilities such as piers, jetties and wharves will be maintained, except where there are safety and security issues. New structures to accommodate access for fishing will be considered where this is supported by the appropriate land manager.

Detailed management proposals for Mallacoota Inlet foreshores, both outside and within the CNP boundaries, are described in the Mallacoota Foreshore Management Plan (EGSC, 2001) and the Croajingolong National Park Management Plan (DNRE, 1996) respectively.

The Mallacoota Foreshore Management Plan (EGSC, 2001) includes proposals to improve boat trailer parking, upgrade recreational infrastructure, and ensure that foreshore activities and developments do not degrade fish habitat.

Management of recreational boating and watercraft

Most of Mallacoota Inlet has been designated as a local port and is managed by Gippsland Ports in accordance with the Port Services Act 1995. Activities within ports are regulated by the Port Services (Local Ports) Regulations 2004. For further information on management of designated local port waters in Mallacoota Inlet, please refer to the Gippsland Ports website:

Boating activities in Mallacoota Inlet are regulated under the provisions of the Marine Act 1988 which is administered by Marine Safety Victoria. Recommendations for changes to boating regulations (including the appropriateness of water-skiing zones and vessel speed limits) in places such as Mallacoota Inlet may arise through public consultation processes conducted by organisations such as local Council or Gippsland Ports.

For further information on boating in this waterway, refer to Marine Safety Victoria – www.marinesafety.vic.gov.au and Gippsland Ports.

The Gippsland Boating Coastal Action Plan (GBCAP) (GCB, 2002) provides direction for the location and scale of boating use and development throughout the Gippsland coast. It also provides a framework for accommodating multiple uses and users of Gippsland waters. GBCAP identifies appropriate boating activities for 'coastal estuaries' such as Mallacoota Inlet are active nonpowered (i.e. sailing), passive non-powered (i.e. Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve Management Plan 15 canoeing) and passive powered boating (i.e. fishing). Active powered boating like water-skiing and fast cruising is identified as being more appropriate in lakes (inland or coastal) and marine waters. The Gippsland Coastal Board (GCB) is due to commence a review of the GBCAP in 2007.

Gippsland Ports (2005) has prepared a Safety and Environmental Management Plan (SEMP) in accordance with the Port Services Act 1995 which identifies all activities within the ports it manages, to ensure that all significant risks are identified and controlled.

Provision and maintenance of foreshore boating facilities and boating navigational aids

East Gippsland Shire Council (EGSC) is responsible for installation, maintenance and management of boat launching facilities around Mallacoota Inlet. Management of designated local port waters including installation, maintenance and management of lighting and navigation aids, is the responsibility of Gippsland Ports.

Karbeethong jetty is managed by Gippsland Ports while the adjacent boat launching ramp is managed by the EGSC. The GBCAP (GCB, 2002) identifies that both the ramp and jetty at Karbeethong are in satisfactory condition, but that the associated car and trailer parking need upgrading as a high priority.

Gippsland Ports manage the Main Wharf and associated slipway, the slipway jetty and the boat launching ramp jetty located at the township of Mallacoota, while EGSC manages the boat launching ramp. Gippsland Ports has confirmed that the slipway has been recently upgraded.

The Gipsy Point jetty is managed by Gippsland Ports, while the EGSC manages the boat launching ramp. Gippsland Ports has recently completed the reconfiguration and rebuilding of the existing Gipsy Point jetty. The GBCAP recommends an extension of the boat launching ramp into deeper water.

The EGSC administers most private jetties in Mallacoota Inlet on behalf of DSE. Other public jetties not specifically mentioned in this section are maintained and administered by either Parks Victoria or DSE.

All swing moorings found within Mallacoota Inlet are licensed through an annual permit system and administered by Gippsland Ports.

Publications including the Draft Boating Facilities Plan, Mallacoota Foreshore Management Plan, GBCAP and the Croajingolong National Park Management Plan are documents which outline specific management objectives and actions for the ongoing maintenance of relevant boating facilities and navigational aids found within the inlet.

Integrated management of Gippsland estuaries

The GCB, in partnership with the West and East Gippsland Catchment Management Authorities, is developing a Gippsland Estuaries Coastal Action Plan.

Coastal Actions Plans (CAPS) are developed under the provisions of the Coastal Management Act 1995 to address coastal issues and implement the objectives of the Victorian Coastal Strategy at a regional level.

The Gippsland Estuaries CAP will aim to provide a strategic framework for the future use, development and management of the major riverine estuaries within the Gippsland region. Implementing the CAP will assist in maintaining or enhancing aquatic and terrestrial environments and biodiversity, while maximising social and economic benefits from use of the estuaries. The Gippsland Estuaries CAP is due to be finalised in 2006.

Artificial entrance openings

The entrance at Mallacoota Inlet can open as a result of both artificial and natural processes. The entrance is sometimes opened artificially when high water levels threaten to have an adverse impact on infrastructure (particularly jetties and boat launching facilities) and land surrounding the inlet.

Currently, DSE and EGSC have the ultimate responsibility for any decision regarding artificial entrance openings at Mallacoota Inlet in consultation with Parks Victoria, Gippsland Ports, DPI (Fisheries Victoria), East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority (EGCMA) and community representatives. All works associated with entrance openings at Mallacoota Inlet are currently managed by DSE.

Entrance opening works may require a Works on Waterways Permit from the EGCMA. A permit is also required from Gippsland Ports in accordance with the Port Services Act 1995 for works within designated waters.

The Gippsland Estuaries CAP will address the issue of artificial openings of the entrance and, in particular, identify the appropriate stakeholders for decision making as well as the development of a decision support system to inform the process.

At a statewide level, a Steering Committee has been formed to prepare an Estuary Entrance Management Support System (EEMSS). The EEMSS will assist managers to decide whether or not to artificially open an estuary entrance and under what conditions. It is anticipated that the EEMSS may be applicable for Gippsland estuaries, including Mallacoota Inlet. Experts in relevant disciplines (including fisheries) and the community will be engaged to ensure that consideration is given to all possible environmental, social and economic impacts and benefits associated with the opening.

A number of options for the management of entrance openings are currently being considered by management agencies at both a statewide and regional level. Management options are expected to be finalised by December 2006.

Management of catchment activities and their impacts

The EGCMA was formed under the provisions of the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 and the Water Act 1989. The EGCMA works with the regional community, industry and government stakeholders to coordinate the development and implementation of strategies for integrated management of land and water resources in East Gippsland – including Mallacoota Inlet and its tributaries.

The East Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy (RCS) identifies issues affecting all land and water within the East Gippsland region regardless of management obligations or ownership.

The RCS identifies six classes of assets; freehold land, state forest, parks, coastal & marine, groundwater, and catchment assets. Threats to the integrity of these assets and actions to manage the assets have been identified (EGCMA, 2005). General threats to the catchment asset class, as identified by the RCS include:

- Effects of inappropriate land use (including planning) on the environment, natural resource production and landscape amenity;

- Agricultural practices leading to offsite impacts and landscape changes; and

- Introduction of pest plants and animals and their potential impacts on the environment as well as natural resource production.

Implementation of management actions in the RCS will rely on a number of agencies and key stakeholders within the region, including DSE, DPI, Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), local government, private landholders and community based programs such as Landcare, Coast Action/Coastcare and Waterwatch.

The East Gippsland Regional River Health Strategy (RHS), is a sub strategy to the RCS. Threats to the health of the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers, the two major rivers flowing into Mallacoota Inlet, are identified in the RHS (EGCMA, 2006), and include:

- Presence of weeds, including willows;

- Loss of riparian vegetation;

- Bed instability and loss of in-stream habitat; and

- Damage to river health from inappropriate development.

Management actions identified through the RHS to address these threats include:

- Control or eradication of exotic vegetation in conjunction with NSW managers, landholders and other agencies;

- Stock exclusion through fencing of riparian vegetation;

- Foreshore and bank revegetation programs; and

- Implement recommendations of the Genoa River Expert Panel report (Brooks et al., 2001).

Movement of sand in the lower Genoa River

After an investigation into sediment sources in the Genoa River, Erskine (1992) found that the major source of sediment in the Genoa catchment was stream channel erosion. Other significant sources include: soil erosion within recently established pine plantations near Rockton; roading activities (particularly reconstruction of major highways in the area); and the potential for erosion resulting from the passage of intense wildfires (Brooks et al., 2001).

The EGCMA established an Expert Panel in 2000 to report on the status of sedimentation in the lower Genoa River.

The Genoa River between Genoa and Gipsy Point is defined as a sand storage zone for sediment that has been transported through the lower Genoa gorge. A channel recovery program for this area has been established and includes an intensive revegetation program. The Expert Panel concluded that "…it is unlikely that the sand in the reach will move in any quantity into the Genoa River estuary or Mallacoota Inlet" (Brooks et al., 2001 page 52).

Management recommendations of the Expert Panel, in conjunction with stakeholders, to address the threat of sediment deposition and movement in the Genoa River include:

- Excluding stock from waterways;

- Maintenance/enhancement of revegetation in riparian zones;

- Re-establishment of vegetation within the channel bed and on the river edge;

- Management of pest plants; and

- Maintenance and enhancement of existing works and vegetation.

River health works undertaken on the Genoa River over the past few years include:

- Establishment of strong cross border partnerships with NSW land managers to ensure an integrated approach to land management;

- Majority of river frontage fenced to promote rehabilitation of the riparian zone and vegetation;

- Willow control program along the Genoa River from the NSW border downstream; and

- Management of the sand slug at Genoa including re-establishment of vegetation in the riparian zone and sand bed, and placement of large pieces of wood within the sand bed for stabilisation.

Aquatic pest plant and animal management

The introduction of exotic organisms into Victorian marine waters has been listed as a 'Potentially Threatening Process' under the provisions of the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 administered by DSE. Action Statements will be developed describing how these and other potentially threatening processes are to be addressed in Victoria. Other listed potentially threatening processes of relevance to estuaries such as Mallacoota Inlet, can be found at www.dse.vic.gov.au. Marine pest emergency response arrangements, known as the "Interim Victorian Protocol for Managing Exotic Marine Organism Incursions", currently form the basis for responding to introductions and incursions of marine pests.

The introduced European Shore Crab and Pacific Oyster have been recorded in Mallacoota Inlet. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that populations of these species have not shown any signs of increased abundance or expansion of their distribution within the inlet. The reasons for this lack of expansion are unclear. Although no formal monitoring programs are in place for these species, observations from recreational fishers will be used to monitor changes of distribution.

Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve Management Plan

The overall purpose of the MIFRMP is to formalise management arrangements for the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve in accordance with the provisions of the Act, the Ministerial guidelines and the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development.

To this end, the MIFRMP specifies goals, objectives, strategies and actions for management of fishing activities in the reserve.

The MIFRMP also identifies processes for management of other non-fishing values and uses of the inlet, and opportunities for fisheries stakeholders to participate in these processes to ensure identification and minimisation of potential adverse impacts on fish habitat and fisheries.

The MIFRMP contains a section describing research and monitoring information needed to address the identified management objectives and performance indicators, a section outlining a strategy for promoting compliance with fishing controls in the inlet, and a section describing implementation and future review processes.

Duration of the MIFRMP

The MIFRMP will provide the basis for the management of the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve for a period of 10 years unless established fishery monitoring and assessment programs indicate a need for a review prior to that time.

Review of the MIFRMP

Review of the MIFRMP and preparation of a new MIFRMP will commence twelve months prior to the scheduled expiry of the MIFRMP. The review will examine all aspects of fisheries management against the defined goals, performance indicators and reference points, and will examine the need for new or amended objectives in light of monitoring and research information obtained.

Should there be a need for the Minister to amend the MIFRMP prior to this review, notice of this intention will be published in the Government Gazette.

The planning process

Requirements of the Fisheries Act 1995

The Act stipulates that a management plan must be prepared for a fisheries reserve as soon as possible after the Reserve has been declared under section 88 of the Act.

Each declared fisheries reserve management plan must:

- define the fishery or fisheries to which it relates;

- be consistent with the objectives of the Act and, in the case of a fisheries reserve, be consistent with the Order in Council declaring the reserve;

- specify objectives for management of the fishery or fisheries covered by the plan;

- specify the management tools and any other measures to be used to achieve the objectives of the plan;

- specify performance indicators, targets and monitoring methods for the objectives and management actions stated in the management plan;

- as far as is known, identify critical components of the ecosystem relevant to the management plan, any current or potential threats to those components, and existing or proposed measures to protect or maintain these ecosystem services; and

- as far as relevant and practicable, identify any other biological, ecological, social and economic factors relevant to the fishery or fisheries covered by the plan including: fishery trends and current status; the socio-economic benefits of fishing and other human uses of the area or resources in question; measures to minimise the impact of fishing on non-target species and the environment; fisheries-related research needs and priorities; and an assessment of the resources required to implement the management plan.

The Act also indicates that each management plan may:

- specify the duration of the management plan;

- specify procedures and or conditions for review of the plan;

- in the case of a fisheries reserve, specify guidelines regulating or restricting activities in the reserve;

- in the case of a fisheries reserve, specify terms and conditions under which any special activities in the Reserve may be permitted; and

- include any other relevant matters.

Additional direction on the development of the MIFRMP has been provided by the gazettal of Ministerial guidelines on 11 May 2005 (see Appendix 3).

Requirements of the Native Title Act 1993

Native Title describes the interests and rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in land and waters according to their traditional laws and customs that are recognised under Australian Law (NNTT, 2000). The MIFRMP is required by law to adhere to the requirements of the Native Title Act 1993 as a part of the planning process which allows Native Title parties an opportunity to comment on the MIFRMP through a 28-day notification process.

Advice on particular situations relating to East Gippsland (particularly Mallacoota Inlet) is available through the Native Title Coordinator at the Traralgon Office of the DSE.

Steering Committee

The MIFRMP was prepared by Fisheries Victoria, assisted by a Steering Committee consisting of an independent chair and representatives from key stakeholders including VRFish, FCC, EGSC, Parks Victoria, EGCMA and Indigenous interests.

The role of the Steering Committee was to advise the Executive Director, Fisheries Victoria, DPI, on the preparation and consistency of the MIFRMP with respect to the requirements of the Act and the Ministerial guidelines, and to assess public submissions from community consultation on the draft MIFRMP.

The Terms of Reference for the Steering Committee and the list of the stakeholder representatives are provided in Appendix 4.

Public consultation

The first step in the preparation of the MIFRMP was to seek the views and comments of recreational fishers and other community interests regarding the values and issues associated with fishing in Mallacoota Inlet.

Two meetings were held in Mallacoota in July 2005 to explore these issues and values. Members of the public and recreational fishers who were unable to attend the meetings were invited to submit their views and comments in writing by the end of August 2005.

Approximately thirty-five written and verbal submissions were received as a result of the initial consultation process. The information collected guided the drafting of the MIFRMP to ensure it had a strong focus on addressing fishing-related issues that matter to both visiting and resident recreational fishers and the local community.

Values and issues raised during the first round of public consultation included:

- Mallacoota Inlet is valued by recreational fishers because it provides a safe environment for shore and boat based fishing, and has reasonable infrastructure and services;

- Mallacoota Inlet is highly regarded as a black bream and dusky flathead fishery. Other identified target species included mulloway, Australian salmon and prawns;

- a proportion of respondents wanted size limits increased for dusky flathead;

- the introduction of a seasonal closure of recreational bream fishing in waters upstream of Gipsy Point (including the Genoa and Wallagaraugh rivers) to protect black bream spawning stocks was proposed; however, others opposed the closure of any waters to recreational fishing;

- a number of individuals indicated they would like to see an increase in locally available information about where and how to catch fish in Mallacoota Inlet;

- concerns were raised about the possible impacts of a variety of habitat and environmental issues on fish production and therefore fishing in the inlet. Issues raised included erosion and sediment deposition from inappropriate land use, foreshore vegetation removal and logging in the upper Genoa and Wallagaraugh catchments; sand movement inside the inlet; closure and artificial opening of the entrance; and water quality in the inlet;

- concerns were raised about the quality and quantity of access to the inlet for both boatbased and shore-based fishing; and

- issues regarding competition and conflict between recreational fishers and other waterbased users of Mallacoota Inlet.

A second round of public consultation calling for comments and views on the Draft MIFRMP was held in early 2006 for a period of sixty days.

Amendments to the MIFRMP were made as a result of the seven submissions received.

Management goals and objectives

The following broad goal and objectives apply to management of fishing activities in the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve.

Goal

To manage Mallacoota Inlet fish stocks and the fisheries they support, and to identify and promote protection of important fish habitats in a manner that is sustainable and which provides optimum social and economic benefits to all Victorians in accordance with ESD principles.

Objectives

- Social – To maintain, and where possible, enhance recreational fishing opportunities in Mallacoota Inlet.

- Biological – To conserve and ensure sustainable use of key fish stocks in the inlet.

- Environmental – To identify and promote protection of the habitats and environments which are essential for production or maintenance of key fish stocks in the inlet.

- Governance – To achieve maximum community participation, understanding and support for the management of fishing activities in the Mallacoota Inlet Fisheries Reserve.

Strategies

More detailed accounts of the strategies, management actions, performance indicators and information needed to address each of these objectives are provided in the following sections and are summarised in Table 2.

Some of the issues raised during the development of the MIFRMP cannot be directly dealt with in accordance with fisheries legislation. For these issues, the MIFRMP attempts to identify other processes whereby recreational fishing interests can ensure their concerns are addressed.

Performance indicators are provided for actions that Fisheries Victoria has direct responsibility for implementing. These indicators provide a means of tracking progress on an ongoing basis.

Performance indicators are not provided for actions that other agencies are responsible for implementing.

Recreational fishing opportunities

Strategy 1 - Monitor fishing values or preferences in Mallacoota Inlet

Recreational fishing-based tourism is considered to be a major contributor to economic activity in small coastal towns such as Mallacoota and Gipsy Point. Available anecdotal evidence and information from recreational fishing surveys (e.g. Hall et al., 1985) suggests that the quality of angling (measured as both numbers and size of fish caught) is considered to be one of the main attractions for visitors to the Mallacoota Inlet area.

Preliminary information obtained from verbal and written submissions during the first phase of public consultation in July 2005 indicated that Mallacoota Inlet is a preferred fishing location because of:

- its proximity to NSW;

- safety of the inlet for boat and shore-based fishing;

- reasonable access for aged or impaired anglers;

- infrastructure and services provided by the township of Mallacoota which supports recreational fishers; and

- range of fish species within the inlet.

Occasional creel surveys of recreational fishing in Mallacoota Inlet conducted since the early 1980s have indicated that bream (mostly black bream) and dusky flathead have been the most popular recreational target species in the inlet for at least the last 25 years. Hall et al. (1985) found that in the early 1980s about 38% of surveyed Mallacoota Inlet anglers specified bream as their primary target species, while about 23% of anglers specified dusky flathead. Fewer than 2% of surveyed anglers nominated any other species as a primary target species, and about one third of anglers were not fishing for any species in particular.

Surveys of Mallacoota Inlet conducted in 2000/01 (as part of the National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey) and in 2004/05 (to evaluate the impact of new stricter dusky flathead catch limits) have confirmed the popularity of bream and dusky flathead as primary angling target species, but have also indicated that targeting of dusky flathead - particularly using artificial lures - has increased much faster than for bream in recent years.

Other information on recreational fishing values or preferences provided by the early 1980s survey included:

- more than 85% of fishing trips to the inlet were by visitors to the Mallacoota Inlet area. Of the local resident anglers, a substantial proportion were retirees;

- there are substantial seasonal fluctuations in recreational fishing effort in the inlet, with peak periods coinciding with public holiday or school holiday periods;

- less than 15% of total recreational fishing effort in the inlet was shore-based with the Bottom Lake slightly more popular for shorebased fishing than the Top Lake;

- prawns and Bass yabbies were the most popular baits for bait fishing in the inlet;

- less than 5% of interviewed anglers were using artificial lures in the inlet in the early 1980s, however anecdotal evidence suggests that in recent years the proportion of anglers using hard body or soft plastic lures has increased significantly; and

- catches of bream dominated in the Top Lake and rivers, while catches of dusky flathead dominated in the Lower Lake.

Ongoing periodic surveys of this kind are needed to provide up-to-date information and to detect changes in the demographic profile of recreational fishers (e.g. proportion of visitors versus local residents, residential origins of visitors) or in the values or preferences individuals attach to fishing in the inlet (e.g. preferred target species, preferred fishing methods, locations and or seasons, and acceptable catch rates for a particular species). This information is required in order to determine what fishers value or prefer in their recreational fishing experiences and, therefore, what fisheries management actions may help to maintain or enhance recreational fishing opportunities.

Information requirements

Surveys of representative samples of Mallacoota Inlet recreational fishers are needed to provide information on fishing values or preferences associated with fishing in the inlet. These surveys need to be conducted periodically to initially benchmark and then detect any changes in fishing values or preferences.

The most cost effective collection of such information is likely to be through periodic attitudinal surveys at fishing access points around the inlet (for visiting and local non-club fishers) and through direct survey of local fishing club members.

Performance indicator

- Information on profile of recreational fishing collected from at least 200 anglers per survey.

Actions

- Fisheries Victoria to establish periodic surveys of anglers to provide information on fishing values or preferences. The first survey to be conducted within the first two years following declaration of the MIFRMP and a minimum of one additional survey in the remaining life of the MIFRMP.

- Fisheries Victoria, in consultation with recreational fishing stakeholders, to evaluate possible fishery management actions to maintain or enhance recreational fishing opportunities based on the results of surveys.