Estuary perch movement and habitat use in the Snowy River

Recreational Fishing Grant Program – Research report

February 2010

John Douglas

Preferred way to cite this publication:

Douglas, J (2010) Estuary perch movement and habitat use in the Snowy River Recreational Fishing Grant Program - Research report. Fisheries Victoria.

ISSN: 1833-3478

ISBN: 978-1-74217-997-1 (print),

978-1-74217-998-8 (online)

For more information contact our Customer Service Centre on 136 186.

Table of contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Methods

Fish collection and tag implantation

Real-time tracking

Long-term movement

Habitat mapping

Results

Real-time tracking

Long-term movement

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

Executive summary

Estuary perch are present in most estuaries along the Victorian coastline. The species is recognised as an excellent sport fish by a growing number of angling devotees.

There is little information known regarding the general movements and specific habitat preference of the species in estuaries. Such information would not only assist anglers to more accurately target this species but also assist identifying key habitat components for estuary perch in estuaries.

This project aimed to provide angler-oriented information on:

- seasonal movement patterns of estuary perch in the Snowy River estuary

- short-term (daily) movement of estuary perch in the estuary

- associations of the species with particular habitats within the estuary. Results of this study found that Estuary perch:

- did not display any strong seasonal movements.

- were active at night but did not move very far during daylight

- travelled extensively around the estuary through a range of habitats but in daylight preferred to stay in the deeper sections of the rivers and snags.

In-stream cover is a very important component of the estuarine habitat for estuary perch.

Introduction

Estuary perch are present in most estuaries along the Victorian coastline. The species is recognised as an excellent sport fish by a growing number of anglers.

For many years estuary perch were virtually unknown except to a few anglers, and even today are generally not caught by the many recreational fishers. However this is rapidly changing as fishing publications report estuary perch angling in articles, and Victorian anglers look for sportfish close to home.

Advancements in lure technology such as 'soft plastics', new angling techniques, fish sounders and the increase in purpose-built or out-fitted boats has seen a growing number of anglers realise the sporting potential of the species. This growing awareness of estuary perch potentially places additional pressure on the resource.

Whilst the general locations where estuary perch might be found are known locally, there is a need for more detailed knowledge of their habitat associations and movement patterns on a seasonal basis as well as through a daily cycle. Researchers and fisheries managers do not understand the patterns of activity and movement of estuary perch on either a long-term or a short-term basis and there is little published information regarding the general movements and specific habitat preference of the species. Such information will inform fisheries managers of any behaviour patterns, for example, increased targeting of effort by anglers on seasonal aggregations of fish. In a broad sense the information will highlight where or if any special management considerations are required.

The results are not expected to be specific to the Snowy River estuary but are expected to apply to similar areas where this species occurs. Identification of the preferred habitat of estuary perch will assist estuarine habitat enhancement for this species.

The project aimed to provide angler-oriented information on:

- seasonal movement patterns of estuary perch in the Snowy River estuary

- short-term (daily) movement of estuary perch in the estuary

- associations of the species with particular habitats within the estuary.

Methods

Fish collection and tag implantation

Recreational anglers assisted in capturing the estuary perch used in the study. A total of 23 estuary perch were caught with single hook lures in October 2003. Upon capture, fish were immediately placed in an oxygenated holding tank and transported to a field-based operating area where the fish were anaesthetised in benzocaine and an acoustic tag was surgically implanted into the abdominal cavity via an incision (<2cm). After tag insertion the wound was sutured and the fish revived in an oxygenated holding tank prior to release. The fish was kept moist throughout the operation and estuarine water was applied to the gills with an atomiser. The operation took under four minutes. Fish were all large enough to keep tag-weight at <2% of the fish bodyweight.

Two types of movement were monitored in the study using two methods:

- Real-time tracking was used for short-term movement monitoring ,

- Fixed listening stations deployed around the estuary were used to monitor the long-term, large-scale movement. The fixed listening stations were also used to investigate diurnal movement patterns.

Real-time tracking

Continuous pinger tags (V13 Vemco, Canada) were used for the real-time tracking work. These tags transmit a regular pulse train on separate frequencies for each fish. The regular transmissions can be used to identify, and accurately locate and track, individual fish over short periods. Eight estuary perch were implanted with continuous pinger tags.

A portable receiver (VR60 Vemco, Canada) and omni-directional hydrophone and boat were used in the real-time tracking. The fish were located by systematically searching throughout the estuary with the hydrophone to detect a tagged fish. The boat was stopped mid-channel every 200 m and the omni-directional hydrophone placed in the water to 'listen' for signals. Once located, the position of the fish was determined by triangulation to within 10 m with a directional hydrophone. The location and time was recorded by a GPS unit (Magellan). Movement between locations was calculated in metres per minute. A t-test was used to determine if there was a statistical difference between distances moved by night and day. The presence or absence of cover at the location of the fish was noted. The fish was followed at a distance and the location noted via the GPS every 30 to 60 minutes. Real-time tracking sessions were undertaken either in daylight and at night (from sunset into darkness). Individual fish were followed and their location recorded at least four times for each tracking session. Tracking sessions varied between 2 to 6 hours.

Long-term movement

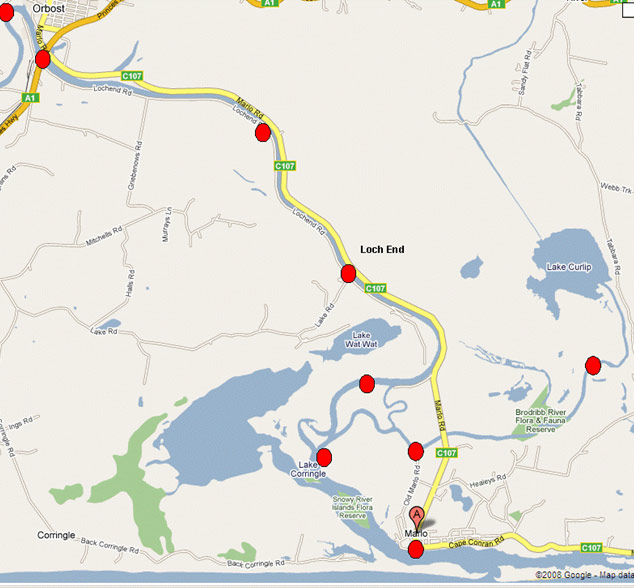

Coded tags (V13SC Vemco, Canada) were used for the long-term monitoring. These tags were all on the same frequency but individually coded with a unique number. The tags transmitted randomly with a delay between transmissions between 30 and 90 seconds. The transmission delay is random to minimise the chance of transmissions from close tags synchronising and, therefore, not being able to be decoded correctly by the receivers. The tags had an expected 240-day lifespan. A series of 9 receivers (VR2, Vemco, Canada) were deployed throughout the Snowy River estuary upstream from the Marlo jetty to Orbost (Figure 1). Details of the receivers are presented in Table 1. In addition to these estuarine located receivers, there were also five transmitters deployed in the freshwater section of the Snowy River from Orbost up to Jacksons Crossing that were being used for a complimentary project focusing on tracking Australian bass throughout the Snowy River. Of the estuarine receivers, seven were spaced out along the Snowy River and two were situated in the Brodribb River. The receivers were attached via heavy galvanised chain affixed to structures such as jetties, pylons and over hanging tree trunks. The receivers were marked with a yellow buoy identifying the device. Signs explaining the project were also deployed around vehicular access points and near boat ramps.

The fixed listening stations decoded the transmissions and recorded the code number as well as the time and date when the tag was in range. The receivers were deployed in October 2003 and the final download of all data was undertaken on December 2005. The VR2s were numbered sequentially upstream from the Marlo jetty (Table 1). A total of 15 estuary perch were implanted with coded tags with identification numbers from 201 to 215(Table 2).

Diurnal activity was explored by counting the number of times a single fish visited two or more receivers in day, night, dawn or dusk. Dawn and dusk were determined as an hour each side of either sunrise or sunset. Sunrise and sunset times were grouped on a monthly basis by the sunrise, sunset times occurring mid month.

Habitat mapping

The estuary bathymetry data were obtained via mapping the lower section of the estuary, from just downstream of the Marlo jetty upstream to Lochend. A commercially produced depth sounder linked to a GPS unit (Ceeducer ProTM, Bruttour International Hydrographic Surveys, Sydney) was mounted on a boat and the vessel driven around the estuary to gather numerous depths and associated GPS coordinates. The transducer and GPS antenna were affixed to each end of a length of PVC pipe that was then attached to the leg of an auxiliary outboard motor. When the auxiliary motor-leg was lowered it offered a secure vertical bracket that held the GPS unit directly above the transducer. The transducer was also protected by the skeg of the auxiliary motor. The Ceeducer unit recorded a depth and location every few seconds.

The date were downloaded and the depth grids were created in Surfer (Golden Software) using the natural neighbour method and a cell size of 5 m. The data were then converted to ArcView Spatial Analyst (Environmental Systems Research Institute Inc.) to create depth contour lines from the grid.

Table 1 Details of the VR2s locations used in the study

| Code No | Location | River distance from sea (km) | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Snowy River-Marlo Jetty | 1.3 | -37.798100 | 148.534745 |

| S2 | Snowy River-u/s Second Island | 4.1 | -37.784517 | 148.512539 |

| S3 | Snowy River d/s Little Snowy | 6.6 | -37.770321 | 148.526322 |

| S4 | Snowy River Lochend | 10.1 | -37.752417 | 148.519283 |

| S5 | Snowy River floodgates | 12.0 | -37.740300 | 148.505367 |

| S6 | Snowy River Orbost bridge | 18.1 | -37.716940 | 148.452585 |

| S7 | Snowy River u/s Butter factory | 19.6 | -37.709717 | 148.446750 |

| B1 | Brodribb River boat ramp | 8.5 | -37.781250 | 148.534167 |

| B2 | Brodribb River below Cabbage tree Ck | 12.8 | -37.767327 | 148.573450 |

Figure 1 Map of Marlo estuary and indicative location of VR2 listening stations (Red dots)

Results

Real-time tracking

Two fish were observed on 11 tracking sessions over six days. Tracking sessions lasted between two and six hours. One fish was tracked for eight sessions and the other for three sessions. For the fish that was tracked eight times, three of the sessions were at night and five sessions were in the day. For the fish that was tracked for three sessions, two sessions were in the day and one at night.

In the upper reaches of the estuary, the daylight habitat areas were either dead willow that had fallen into the stream or underneath overhanging live willow branches. These habitats were within 5 m of the shore and in water less than 2 m deep. These areas were also the deeper sections of the stream in the immediate area.

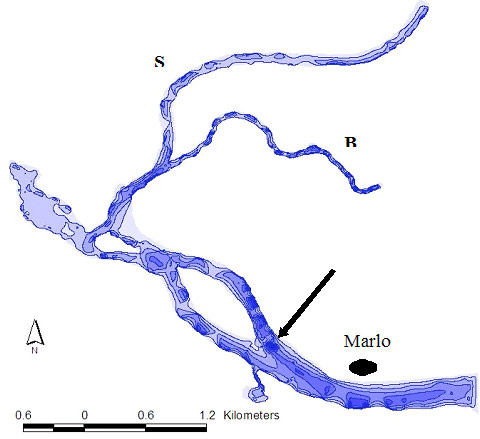

In the lower estuary, the daylight habitat was in the deeper section of the estuary away from the bank. Fish were regularly located in an area to the east of the boat ramp. The bathymetry of the estuary in that area indicated a deeper section of the estuary (Figure 2).

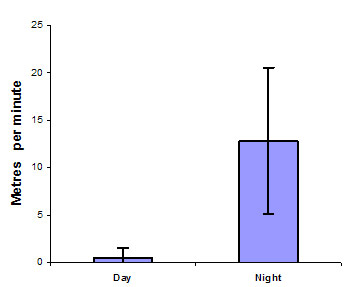

Activity levels of these real-time tracked estuary perch varied between night and day (p= 0.00184) with more distance travelled at night. A comparison of the activity as mean distances travelled in day and night derived from both observed fish is presented in Figure 3.

At night both fish travelled some distance (up to 3 km river distance) in the periods that they were monitored. The highest speed measured for these active fish was 1.2 km/hour. During the early night the fish roamed continuously without stopping. The fish sometimes travelled near shore and sometimes in the middle of the river.

In general, fish did not return to the same daytime location. There was only one instance out of the seven daytime tracking events where a fish was observed at the same daytime location on consecutive days. This fish was tracked on two consecutive evenings and followed the same movement path until it was unable to be followed into a very shallow lake.

Long-term movement

Estuary perch were monitored from November 2003 to September 2005. Mortality estimates for the study were low. A total of 13 estuary perch out of the fifteen tagged were re-detected throughout the study.

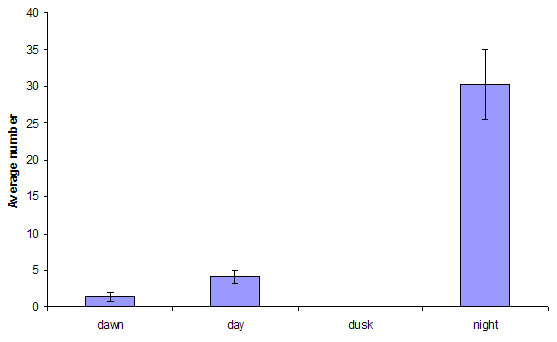

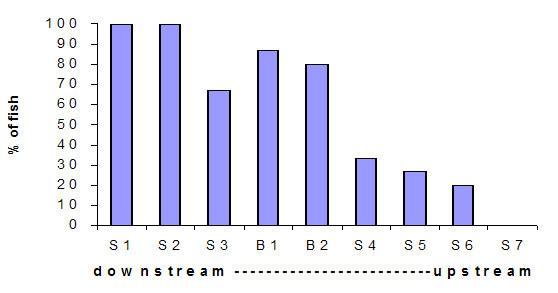

No fish were reported as caught by recreational anglers. Fish #206 went missing four days after release and may have died or the tag failed. Fish #214 was seen for ten months and was last detected on 28 August 2004 on the upper Brodribb River VR2. It is possible that the fish was still alive at the end of the study but upstream of the VR2 and out of range. The other fish were regularly detected throughout the study. Diurnal habits were also observed in the long-term monitored fish. More movement (defined by any single fish visiting two or more receivers) was significantly higher at night than during the day (p<0.001) (Figure 4). Estuary perch used much of the estuary but frequented the lower reaches. The percentage of tagged fish recorded at each VR2 location is presented in Figure 5. All the tagged estuary perch visited the lower reaches of the Snowy River. The percentage of tagged fish visiting other listening stations in the Snowy River declined with distance upstream and only 20% of the tagged estuary perch visited the Princes Highway bridge. No fish were recorded at the top site above Orbost (Figure 1) or any of the receivers deployed in another project to monitor Australian bass.

Over 80% of estuary perch visited the two Brodribb River sites. The lower reaches of the Snowy River (and the Brodribb River downstream of Lake Curlip) appear to be the main areas where estuary perch were found.

On an individual basis, estuary perch movement was found to be quite variable as the incidence of listening stations visited by individual estuary perch ranged from 33% to 89%. Some fish actively moved around the estuary while others were more sedentary. No tagged fish visited all the listening stations.

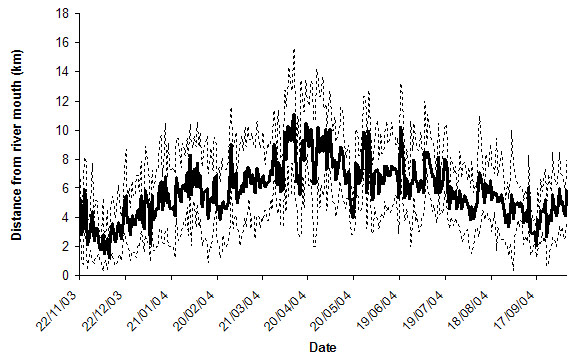

Seasonal movement was investigated by comparing the location of the fish (as average distance from the sea) by date. There was some inclination for the estuary perch to move further away from the river mouth in the autumn (Figure 6) but it was not significant (p>0.005).

Table 2 Details of estuary perch used in long-term movement study

| Length (mm) | Weight (g) | Tag No. | Release date | Release point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 410 | 1170 | 201 | 22/11/03 | Brodribb R |

| 442 | 1440 | 202 | 22/11/03 | Brodribb R |

| 390 | 934 | 203 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 370 | 894 | 204 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 330 | 648 | 205 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 382 | 932 | 206 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 360 | 717 | 207 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 330 | 604 | 208 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 339 | 683 | 209 | 22/11/03 | Snowy/Brodribb junction |

| 334 | 663 | 210 | 25/11/03 | Brodribb boat ramp |

| 365 | 810 | 211 | 25/11/03 | Brodribb boat ramp |

| 326 | 578 | 212 | 25/11/03 | Brodribb boat ramp |

| 344 | 695 | 213 | 25/11/03 | Brodribb boat ramp |

| 410 | 1175 | 214 | 25/11/03 | Brodribb boat ramp |

| 420 | 1289 | 215 | 25/11/03 | Brodribb boat ramp |

Figure 2 Diagram of a section of the lower Snowy River estuary (S- Snowy River, B- Brodribb River) with bathymetry derived from Ceeducer (1 metre contours). Arrow indicates deeper area used by some estuary perch in daylight hours in the lower estuary.

Figure 3 Comparison of the mean distance travelled per minute by estuary perch between night and day. Error bars are standard deviation (n= 11 observations from 2 fish over 11 tracking sessions)

Figure 4 Comparison of average number of occurrences where two or more VR2 receivers were visited by a single perch by time of day

Figure 5 Percentage of tagged estuary perch recorded at VR2 listening stations laterally along the Snowy River estuary.

Figure 6 Average distance from river mouth of estuary perch by date. Dotted lines indicate upper and lower 95% confidence limits.

Discussion

The aims of this project were to provide information on the seasonal movement patterns of estuary perch in the Snowy River estuary, the short-term (daily) movement patterns of estuary perch in the estuary, and to identify any associations of the species with particular habitats.

Individual estuary perch were found to be highly mobile but their movement patterns appeared to be fish specific with no seasonal spawning or tidal influenced trends evident. This contrasts with earlier studies where estuary perch movement was tidally driven, restricted to short distances (especially at night) or seasonal movements of mature fish for spawning (McCarraher and McKenzie 1986, McCarraher 1986).

McCarraher (1986) suggested that estuary perch migrate downstream to spawn in the lower estuary; he also suggested movement occurred between estuaries. This was not observed in the present study as no fish were suspected to have left the estuary (i.e. last record on lower most receiver). There was a slight but not significant trend of fish being lower in the estuary in spring and early summer and further upstream in April-May. In Victoria, estuary perch spawn in the lower reaches of the estuaries during November-December (Cadwallader and Backhouse 1983). The slight trend in estuary perch movement observed in this study may be influenced by spawning.

The lower estuary was visited by all the tagged fish whereas the listening stations located in the upper reaches of the estuary only detected a few of the tagged fish. These lower areas tend to be the deeper parts of the system as the Snowy River upstream of Lochend has been in-filled with sand and becomes quite shallow. In general, this study indicates that estuary perch appear to prefer the lower part of the Snowy River estuary and the Brodribb River. However, as the fish move throughout the whole estuary up to Orbost, they could be located by anglers at any location at any time.

In daylight hours, estuary perch were found to associate with in-stream cover or the deeper areas of the estuary, were not mobile and tended to stay in the one location for the whole day. Irrespective of location, the estuary perch preferred the deeper areas. For example, some fish were located in willow snags near the Lochend boat ramp. The river in the Lochend area is generally shallow (<1 m) across much of the channel and the perch were in the cover in the slightly deeper section (<2 m) of the channel near the river margin. At night, estuary perch tend to become mobile and move throughout the estuary. Once mobile, they could be encountered in a range of habitats including areas away from cover. Fish were tracked swimming mid-channel as well as along the stream margins.

In estuaries there are many driving forces that could impact fish movement such as spawning migrations, food availability, oxygen and or salinity concentrations/gradients, light intensity and tides. Strong tidal movements may result in larger changes in salinity throughout the estuary and therefore may have more impact on fish distribution than estuaries with less tidal influence. Salinity is a major factor that influences estuarine fish distribution and assemblage in estuarine systems (Edgar et al. 1999, Barletta 2005) although water oxygen levels can also be a factor, particularly in estuaries with small water exchange (Peirson and Frear 2003). Wright et al. (1990) reported that the effects of tides on fish movement could be so strong that it could even mask any diurnal movement patterns.

At the time of this study there was little tidal movement in the estuary as there were generally low water flows in the Snowy River and the entrance was severely restricted by sand. This prevented large exchanges of water between the ocean and estuary and consequently caused little tidal run. We saw no influence of tides on movement as only diurnal fish movement was observed. It appeared that the low tidal exchange in the Snowy River estuary over the period of this study had little impact on fish movement. The daily movement patterns observed indicated the fish were particularly active at night supporting the findings of McCarraher and McKenzie (1986) but the results contradict their suggestions that movement is related to tides. In our study the movement of estuary perch was principally nocturnal and thus related to light intensity and time of day - and not the tides.

The association of estuary perch with water depth and in-stream habitat in daylight hours reconfirms the importance of such habitat in estuarine systems for the species. Therefore, any efforts that protect and/or enhance such habitat should be encouraged. It is possible that the sand in the stream bed above Lochend has reduced depth and, therefore, restricted perch habitat in this reach. This may influence the distribution and behaviour of estuary perch to stay in the lower reaches of the Snowy River and Brodribb River as seen in this study.

Conclusions

This project aimed to provide angler-oriented information on:

- seasonal movement patterns of estuary perch in the Snowy River estuary

- short-term (daily) movement of estuary perch in the estuary

- associations of the species with particular habitats within the estuary

Estuary perch did not show predictable patterns of long-term (seasonal) movement. There was a slight tendency for the estuary perch to be lower in the estuary in spring and early summer and further upstream in April-May but this was not significant.

Estuary perch are nocturnal and move extensively around the estuary at night. Estuary perch movement has been related to tides but during this investigation tidal exchange was low, and no correlations between tides and movement was observed.

In daylight hours estuary perch were found to associate with in-stream cover or the deeper areas of the estuary. Cover, in the form of snags, overhanging trees or deep water is an important habitat feature to estuary perch.

Estuary perch preferred the lower sections of the Snowy River estuary downstream of Orbost and the lower reaches of the Brodribb River downstream of Lake Curlip. A few fish travelled upstream of Lochend but no estuary perch travelled into the freshwater sections of the Snowy River upstream of Orbost.

Acknowledgements

David Ball at the Department of Primary Industries, Marine and Freshwater Systems Platform, Queenscliff campus constructed the depth contours and along with Sean Blake, answered many GIS related queries. Kylie Hall, Paul Brown and Wayne Fulton provided comments on the manuscript. Kaj Busch and Helmut used their considerable skills and angled the fish used in the trials.

This project is funded by the Victorian Government using Recreational Fishing Licence Fees.

References

Barletta M, Barletta-Bergan A, SaintPaul U and Hubold G (2005). The role of salinity in structuring the fish assemblages in a tropical estuary. Journal of Fish Biology 66 pp 45-72.

Cadwallader PL and Backhouse GN (1983). A guide to the freshwater fish of Victoria. Fisheries and Wildlife Division, Ministry for Conservation. Victorian Government Printing Office.

Edgar GJ, Barrett, NS and Last PR (1999). The distribution of macroinvertebrates and fishes in Tasmanian estuaries. Journal of Biogeography 26 pp 1169-1189.

Lucas MC and Baras E (2000). Methods for studying spatial behaviour of freshwater fishes in the natural environment. Fish and Fisheries 1 (4), 283-316.

McCarraher DB and McKenzie JA (1986). Observations on the distribution, growth, spawning and diet of estuary perch (Macquaria colonorum) in Victorian waters. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series 42. 21 pp.

McCarraher DB (1986). Distribution and abundance of sport fish populations in selected Victorian estuaries, inlets, coastal streams and lakes. 2. Gippsland Region. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series 44. 35 pp.

Peirson G and Frear PA (2003). Fixed location hydroacoustic monitoring of fish populations in the tidal River Hull, north-east England, in relation to water quality. Fisheries Management & Ecology 10 (1), 1-12.

Wright JM, Clayton DA and Bishop JM (1990). Tidal movements of shallow water fishes in Kuwait Bay. Journal of Fish Biology 37 pp 959-974.