Direct value of the recreational SBT fishery in Portland

4.1 Introduction

Recreational anglers will place additional value on their recreational experience that is beyond what they have to currently pay to access the fishery. This section presents consumer surplus per angler fishing day estimates, which is the value that any given angler would be willing to pay above the current costs of accessing the SBT fishery in Portland for a day of recreational fishing.

The full value of the 2012 recreational SBT season as a whole is then obtained by extrapolating the estimates of the expenditure and consumer surplus value per angler fishing day. For this purpose, the following three extrapolation approaches, based on the best available data at the time of this study, are used:

- survey data on charter boat operators' customer numbers over the SBT season;

- historical data from a previous DPI study 'Counting the Catch'; and

- combining trailer count data with the daily interview-trailer count ratio.

Finally, the extrapolation approach is applied on the valuation of the recreational SBT fishery in Portland in 2011 in order to verify that current results align with those from previous DPI's 'Counting the Catch' study (validation applicable to methods 1 and 3).

4.2 Consumer surplus per angler fishing day

The following two approaches were used individually to estimate the additional 'consumer surplus' value that anglers place on recreational fishing:

- Consumer surplus derived from the demand for fishing days using the Travel Cost Method (TCM); and

- Willingness-to-pay estimates elicited directly from the Contingent Valuation questions (CVM).

The application of both approaches is consistent with the work presented in relevant literature, such as Cameron (1992) and, Herath and Kennedy (2004). A comparison of the estimates using both techniques is outlined in the following sections.

4.2.1 Consumer surplus derived from the Travel Cost Method

The Travel Cost Method is based on establishing a relationship between visit frequency (in this case, number of fishing days) and anglers' current travel expenditure per angler fishing day, as described in Section 3.3. This relationship, also known as the Trip Generation Function, is estimated using standard econometric techniques and is valid under the status quo, i.e. no access fees to the SBT fishery. The relationship is then re-evaluated by assuming hypothetical price increases to access the fishery. In this way, it is possible to derive the full demand for fishing days in the SBT fishery in Portland or, in other words, the expected visit rate to the SBT season in Portland under a range of price scenarios.

The consumer surplus can then be calculated as the full value of anglers' willingness to pay above the price they currently pay for accessing the fishery (refer to Appendix G for details on the calculation of the consumer surplus).

There are two types of travel cost models that can be used to estimate the consumer surplus:

- Individual travel cost models estimate the relationship between visit rate and expenditure based on the observations of individual anglers; and

- Zonal travel cost models cluster anglers into groups according to their travel distance and estimate the same relationship based on average group visit rate (given by the proportion of the resident population visiting from a given zone) and expenditure.

Selection of the most appropriate model depends on the relative variation in the data, particularly in the number fishing days and expenditure across anglers. Occasional anglers are better modelled with zonal models, whereas frequent anglers are usually more suitably modelled with individual travel cost models. Our empirical analysis indicates the zonal approach is better suited to model the underlying data of visit rate and travel costs expenditure in the SBT fishery, as explained in the box below.

The consumer surplus estimates based on the zonal travel costs model are in the order of $70 to $98 per angler fishing day, according to the specification of the functional form used in the econometric analysis. Additional sensitivity checks were performed on the assumptions used in the calculation of the consumer surplus around the definition of zones (such that a larger number of observations for each zone could be used) and a selection of data points according to their travel costs (i.e. ensuring travel costs are within the main distribution across the sample). The best estimate and range of estimates found are reported in Table 4.1.

| Demand models used for angler fishing days | Range |

|---|---|

| Zonal model: linear specification | $45.73 - $162.20 |

| Zonal model: semilog specification | $75.36 - $95.52 |

| Zonal model: log- log specification | $58.00 - $74.72 |

| Mean consumer surplus estimate (per angler fishing day) | $81.42 |

Econometric estimation to model the demand for recreational fishing

The consumer surplus estimates are conditional on the functional form used to model the Trip Generation Function (TGF), which relates the visit rate, in terms of the number of fishing days per year, to the travel expenditure. This relationship is the core to constructing the demand function for recreational fishing.

In order to obtain an unbiased estimate of this relationship, it is important to account for any potential key determinants that are likely to affect anglers' choices for the number of fishing days in 2012. Various specifications of individual travel cost models incorporating a set of variables were tested, but none of these models showed a statistically significant relationship with travel expenditure, reflecting large variation in the data (as a result, zonal models were used for the TCM instead). However, individual models showed that anglers living in Portland spend more fishing days as compared with visitors, as expected. In addition, anglers on private boats or driving their own car to Portland exhibit larger visit rates than anglers on charter boats or not driving. Finally, anglers with catch and release practices targeting SBT also have a positive correlation with additional fishing days in Portland.

Limitations of the Travel Cost Method

The travel cost method has been used widely and is acknowledged as one of the first environmental valuation techniques, available to economists since the middle of last century. However, the estimates of the willingness-to-pay for a fishing day are limited by the observed expenditure, and the approach also relies on the assumption that anglers will respond in the same way to increases in travel costs and in prices to access the SBT fishery. The method also does not account for any possible substitution effects and changes in budget constraints.

Contingent Valuation techniques address some of these limitations by directly eliciting values from anglers. The estimates of the consumer surplus from the Contingent Valuation Method thus may provide a more complete picture of the value anglers place on their enjoyment for recreational fishing, but there is also the risk of obtaining biased or misleading information if the survey design is not appropriate.

4.2.2 Additional consumer surplus from Contingent Valuation

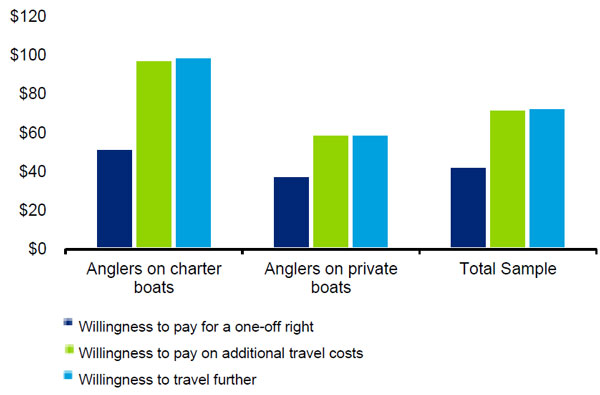

The additional willingness to pay for recreational fishing in the SBT fishery represents anglers' additional recreational surplus value, which has not been realised through anglers' current expenditure so far. For the purpose of this project, the mean additional value of what each angler is willing to pay above their current expenditure is a direct economic value to be compared with previous travel costs consumer surplus estimates. Effectively, the increase in travel expenditure simulates changes in access fees, which then directly define the demand function for fishing days. The estimates of additional willingness to pay are summarised in Table 4.2.

|

Anglers on charter boats |

Anglers on private boats | Total Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Willingness to pay for a one-off right to secure SBT for recreational fishing | $52.22 | $38.20 | $42.91 |

| Willingness to pay on additional travel costs per day to travel to Portland for the SBT season | $98.09 | $59.62 | $72.55 |

|

Per day expenditure associated with the willingness to travel further for SBT (assuming $0.25/km on a return trip) | $99.60 | $59.69 | $73.15 |

Chart 4.1: Elicited consumer surplus values from contingent valuation

4.2.3 Final consumer surplus estimates per angler fishing day

The final value of consumer surplus per angler fishing day consists of the observed travel expenditure modelled with the Travel Cost Method. Alternatively, the additional willingness to pay can be elicited directly by anglers through the Contingent Valuation.

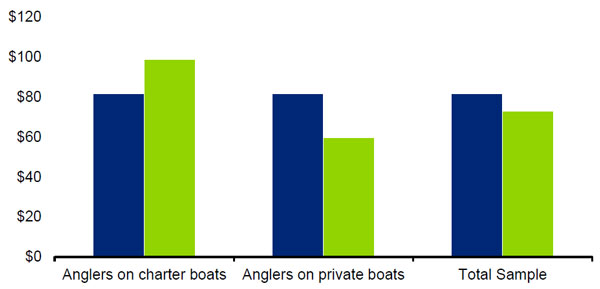

Our per-angler fishing day consumer surplus and willingness to pay estimates are shown in Chart 4.2 below. They are in the order of $59.60 to $81.42 for anglers on private boats and about to $81.42 to $98.90 for anglers using charter boats. The average on the full sample yields a consumer surplus value of $72.90 to $81.42 per angler per fishing day in the SBT season.

Chart 4.2: Consumer surplus values per angler fishing day

4.3 Value of the 2012 recreational SBT fishery

Having arrived at a $ per angler fishing day on the basis of 497 survey responses, the extrapolation challenge is to apply the per angler figure to all fishing trips throughout the year, to yield an annual value. This requires an estimate of the annual number of individual angler fishing days.

4.3.1 Alternative extrapolation approaches

Based on the data available, there are three distinct options for estimating the annual total (and extrapolating to an annual fishery value figure):

- Method 1: Whole-of-year activity estimates provided by charter boat operators;

- Method 2: DPI's 'Counting the Catch' data; and

- Method 3: Combining trailer count data with daily interview-trailer count ratio.

These three approaches and associated estimates of the value of the 2012 recreational SBT fishery are discussed in more detail below.

The use of licences sold was another approach that was considered for extrapolation. Latest data provided by DEPI shows that 256 licences were sold in Portland between January and July 2012 (details are provided in Appendix G), but only 13 anglers (2.6%) from our sample said that they had bought a licence in Portland on the survey day. As anticipated, these figures are too low to be considered representative or allow for extrapolation.

Method 1: Whole-of-year activity estimates provided by charter boat operators

The first method for extrapolation involves the use of whole-of-year activity estimates provided by charter boat operators as part of this survey. According to 20 representatives from charter boat operators, which represent all charter boat operators that are active in Portland during the 2012 SBT season, there were an estimated 6,460 angler fishing days on charter boats during the 2012 SBT season.21

Assuming that the survey of 497 recreational anglers resulted in a random distribution of anglers on charter boats and anglers on private boats, the survey sample (based on the anglers interviewed) assumes that for every angler of a charter boat, there are two anglers on a private boat (i.e. a 34%/66% distribution). Based on this distribution, the number of total angler fishing days in the 2012 SBT season can be extrapolated by applying the distribution to the whole-of-year activity estimates provided by charter boat operators. This provides an estimate of 19,226 angler fishing days in 2012.

Estimate Method 1b = 6,460/33.6% = 19,226

This estimate can be adjusted by taking into account the different number of anglers on private boats and charter boats, to derive a 43.7%/56.3% distribution of anglers on charter boats to anglers on private boats. Based on this adjusted distribution, the estimate would amount to 14,797.

Estimate Method 1b = 6,460/43.7% = 14,797

Further adjustments could be made taking into account other survey findings (e.g. assumed maximum number of anglers over the survey period or angler fishing days over the season). However, the introduction of additional variables increases the level of uncertainty, especially as it combines data from different information collection approaches. As those additional adjustments are likely to result in a substantial overestimate of the number of angler fishing days for the 2012 SBT season, estimates were limited to the more conservative range of between 14,797 and 19,226 for Method 1.

Method 2: DPI (2012) 'Counting the Catch' data

The second approach to extrapolation involves the use of DPI's 'Counting the Catch' (DPI, 2012) data. The DPI study focused on catch and provided the first estimate of the recreational catch of SBT from Victorian waters. DPI estimated that 5,234 (± 772 estimated standard error) boat trips were undertaken in Portland in the 2011 SBT season. The estimate was based on 2,008 interviews undertaken over 101 survey days between March and July 2011 in South West Victoria. However, the survey did not split boats into private boats and charter boats.

Assuming an average of 3.8 anglers per boat trip (based on the survey of recreational anglers undertaken as part of this study and not taking into account potential adjustments discussed in Section 3.5), the number of total angler fishing days in the 2012 SBT season can be extrapolated on the basis of the 2011 DPI data. Assuming little change in the number of boat trips between 2011 and 2012, this provides an estimate of 19,889 angler fishing days in 2012:

Estimate Method 2a = 5,234*3.8 = 19,889

Although the DPI study did not explicitly distinguish between types of boats, it included trailer count information. According to the study, there had been 4,238 boat trailers in Portland in 2011. Assuming that boat trailers represent private boats, we can split the total number of boats into private and charter boats based on the trailer count information and estimate the total number of anglers based on different number of anglers on private and on charter boats:

Estimate Method 2b = 4,238*3.2 + (5,234-4,238)*4.9 = 18,442

Method 3: Combining trailer count data and interview-trailer count ratio

The third approach to extrapolation combines the responses to the survey of recreational anglers with trailer count data provided by AFS Smart Askers as part of this study.

Follow-up discussions with charter boat operators suggests that the SBT season spanned effectively over a maximum of 100 days in 2012 (i.e. this was the maximum of number of days any charter boat operator operated, although based on the survey they expected to operate for a maximum of 130 days in Portland in 2012). On the basis of 20 survey days during which interviews were undertaken (while providing a representative sample in terms of seasonality) over the 2012 SBT season, our data represent 20% of the 2012 SBT season (as discussed in Chapter 2).

No data were available on the seasonality of the 2012 SBT season. However, anecdotal evidence from anglers and operators suggests that the season started slow and peaked towards the end of the survey period (i.e. around mid-June). This is somewhat delayed as compared with the 2011 season, which – based on the responses to the 2012 DPI study – appeared to have peaked in May. While the response rate is also affected by weather (particularly wind) and days of the week, the pattern in the response rate to the survey of recreational anglers reflects the pattern suggested by anecdotal evidence. Hence, for the purpose of the extrapolation and with the limitations discussed in Section 3.5, the survey is assumed to provide a representative sample of the entire season.

During the 20 survey days, at least 497 boat trips were undertaken with an average of 3.8 anglers on board. This corresponds to a total of 1,889 angler fishing days over the 20 survey days or an estimated 9,443 angler fishing days over 100 days. Based on follow up phone conversations with ten charter operators, it was found that the actual duration of the 2012 SBT season was shorter than anticipated mainly due to weather and economic downturn conditions leading to less bookings being made.

On quiet (bad weather) days, when people from all boats could be surveyed, the sample reflects the number of boat trips on that day. On busy (good weather) days, there were generally more boats than could be surveyed and daily trailer count forms were employed to obtain an estimate of how many boat trips were actually undertaken. Over the 20 survey days in the 2012 SBT season, 1,302 trailers were counted22. Of those, 1,178 were counted on the nine busy days during which 285 anglers (57.3%) were interviewed (see Appendix D for more details). The trailer count number obtained over the 20-day survey period is broadly in line with the trailer counts provided in DPI (2012) for the 2011 SBT season, which amounts to a total of 4,238 trailers counted over 101 days from March to July 2011.

Trailer count data indicate that the angler fishing days estimated on the basis of the survey of recreational anglers is likely to be an underestimate as more boat trips were undertaken on busy days (9 out of 20 survey days had trailer counts exceeding the number of interviews conducted on those days). Between 70 and 290 trailers were counted on busy days when between 21 and 48 interviews were conducted. The interview/trailer count ratio on those days is an average 24% (i.e. interviews were undertaken with representatives from 24% of the boats that were in use that day), hence overall the number of angler fishing days could be around 1.86 times higher than the number of angler fishing days from the survey.

Combining those assumptions, this provides an estimate of 17,564 angler fishing days in 2012:

Estimate Method 3 = (497*3.8)/20%*1.86 = 17,564

Conclusion

All approaches to extrapolation are surrounded by a level of uncertainty and have a number of pros and cons, as outlined in Table 4.3. However, the fact that the three alternative methods to extrapolation produce estimates of a similar magnitude adds some confidence around the estimates.

Methods 1 and 2 are preferred to method 3 due to the significant level of uncertainty surrounding the trailer count. All methods suggest that the number of angler fishing days in the 2012 SBT season could be between 14,797 and 19,889.

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| Method 1: Whole-of-year activity estimates provided by charter boat operators |

|

|

| Method 2: DPI's 'Counting the Catch' data |

|

|

| Method 3: Combining trailer count data with interview trailer-count ratio |

|

|

4.3.2 Estimation of the value of the 2012 recreational SBT fishery

Section 3.3 estimates the average expenditure per angler fishing day over the 2012 SBT season as $381.08. Multiplying this figure by between 14,797 and 19,889 angler fishing days in 2012 provides an estimate for the industry value of the 2012 recreational SBT fishery in Portland of between $5.64 million and $7.58 million.

After accounting for the anglers' additional willingness to pay based on the survey's willingness to pay responses, the estimated value of the industry could increase by $73 per angler fishing day (or $1.08 million to 1.45 million in total) to between $6.72 million and $9.03 million in 201223.

Anglers caught and kept an average 1.4 SBT per angler fishing day, so this amounts to $272 per fish or, assuming a likely weight of a SBT to be between 10kg and 20kg, between $14 and $27 per kg (or between $17 and $32 when including additional willingness to pay). However, fish can vary in size and a 122-kg SBT was caught in the 2012 season24. Compared to around $25 to $30 per kg for commercial SBT catch25, the recreational SBT fishing experience provides a comparable value on a per-fish kept basis. Of course, catch and release fishing means that each fish can be a non-consumptive resource, with a recreational value that is not limited to once only catch like it is with commercial fishing.

4.4 Value of the 2011 recreational SBT fishery

The approach to valuing the 2012 recreational SBT fishery can be extended to produce a hindcast estimate for the value of the 2011 recreational SBT fishery in Portland – primarily to align with DPI's 'Counting the Catch' study.

The 2011 value may differ from the 2012 value as a result of:

- a difference in the average expenditure per angler fishing day;

- a difference in the number of angler fishing days in the 2011 SBT season; or

- a combination of the two.

No additional data are available to revise the expenditure estimates, so the average expenditure per angler fishing day is assumed to be the same as in 2012: $381.08. However, additional data sources can be utilised to adjust the basis for extrapolation and thus refine the 2011 estimate of the number of angler fishing days:

- The survey of charter boat operators provides an estimate for the number of customers they had during the 2011 SBT season. According to representatives from 22 charter boat operators still operating in 2012, there were a total of 6,370 anglers on charter boats in 2011 (compared with 6,460 in 2012). This affects extrapolation method 1.

- The DPI 'Counting the Catch' study already provided an estimate of boat trips in 2011: 5,234. However, no estimate was provided on the average number of anglers per boat in 2011. Hence, method 2 is already current.

- The survey of charter boat operators provided an estimate for the maximum length of the 2011 SBT season of 164 days (compared with 130 days in 2012). This affects extrapolation method 3.

- The DPI 'Counting the Catch' study suggests that the shape of the 2011 SBT season differed to 2011, starting earlier and peaking in May rather than in mid-June.

- Furthermore, anecdotal evidence suggests that there were up to 300 trailer boats observed operating out of Portland in 2011 and 28 charter boats operating out of the region26 (compared with 25 charter boats operated by 22 operators and up to 290 trailers on busy days observed in 2012).

Assuming other assumptions remain unchanged, the three extrapolation methods can be revised as follows to derive estimates for angler fishing days in 2011:

- Estimate Method 1a = 6,370/33.6% = 18,958

- Estimate Method 1b = 6,370/43.7% = 14,590

- Estimate Method 2a = 5,234*3.8 = 19,889

- Estimate Method 2b = 4,238*3.2 + (5,234-4,238)*4.9 = 18,442

- Estimate Method 3 = (497*3.8)/12%*1.86 = 29,273 (not accounting for additional operators or seasonal differences in 2011)

As previously discussed, methods 1 and 2 are preferred to method 3. However, method 3 combined with the anecdotal evidence suggests that recreational fishing activity during the 2011 SBT season may have exceeded that of 2012. Assuming a range of between 14,590 and 19,889 angler fishing days during 2011, the value of the 2011 recreational SBT fishery in Portland can be estimated as between $5.6 million and $7.6 million.

According to the 2012 DPI 'Counting the Catch' study a total of 19,205 SBT fish or 239.6 tonnes of catch were retained by recreational anglers in Portland in 2011. Using those estimates, the 2011 value per fish amounted to between $290 and $395 (compared with $293 to $395 in 2012) or, at 12.5kg per fish, between $23 and $32 per kg (the same as in 2012). As noted before, in addition to the uncertainty around the actual number of angler fishing days in 2011, those estimates are surrounded by uncertainty around whether expenditure per angler fishing day in 2011 is similar to that in 2012.

Footnotes

21 Charter boat operators provided an estimate of the days they had operated in Portland during 2012 along with an estimate of the days that they expect to operate in the remainder of the SBT season in Portland (which added up to 44.5 on average). They also provided an estimate of the average number of customers on each fishing trip (5.6 on average). Angler fishing days per charter boat operator ranged from 60 to 640 during 2012 (or 269.2 on average).

22 Appendix D provides a summary of interviews conducted and trailers counted on different survey days. The data collected does not provide a sufficient basis to make any assessment around whether some visitors were in Portland on bad weather days, but did not go fishing. For instance, weekends either included only good weather days or only bad weather days. Some weather variation occurred during weekdays, but it is impossible to know whether those days were identical in every way other than the weather factor and whether people were present on the bad weather days, which typically occurred prior to the good weather days. The only day that stands out as potentially having had people in Portland who planned to go fishing but did not because of the weather was Queen's birthday (11 June 2012). At the same time, people may have left Portland early because of the weather, so any assumptions around anglers present in Portland would be speculative at best.

23 This potential direct contribution is the sum of the 2012 value for the recreational fishery ($5.64 million to $7.58 million) and the extrapolated additional willingness to pay ($1.08 million to $1.45 million).

24 http://www.theage.com.au/environment/animals/it-was-this-big-monster-tuna-no-fishy-tale-20120530-1zimc.html

25 Conservative estimate following SARDI (2012) and OBPR (2012): in 2002/2003, SBT farms based in the Port Lincoln area produced around 9,000 tonnes of tuna valued at over $255.6 million - equivalent to $28.4 per kg, while in the 2009-10 season, the total SBT aquaculture production output value (i.e. market value) was $102.2 million (for 4,015 tonnes of SBT) – equivalent to $24.9 per kg.

26 http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/images/stories/documents/mediareleases/2012/120420_Walsh_-_Fishing_for_the_value_of_southern_bluefin_tuna.pdf