Lake Hume Fishery Assessment

Recreational Fishing Grant Program – Research report

MARCH 2010

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Methods

- Benchmark current fishery

- Creel survey July 2005- June 2006.

- Stocking of trout

- Determination of angler typology

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

Appendix 1

Executive Summary

The management responsibility for recreational fisheries in Lake Hume has been transferred from New South Wales Fisheries (NSW Fisheries) to Fisheries Victoria (FV). The lake contains a significant fishery; however, FV had little information on either its fish stocks or its anglers. To rectify this situation, fisheries dependant and independent assessments were undertaken on the Lake Hume recreational fishery.

The results indicate that Lake Hume is primarily a popular and productive redfin fishery. Although brown trout, golden perch and Murray cod have been stocked into the lake by FV—and these species were present in the fishery independent samples—they did not appear in angler catches in any significant numbers. These fisheries are considered to be generally under-utilised by recreational fishers.

The Lake Hume trout fishery was primarily maintained through natural recruitment and additional stocking each year by FV.

Trout in the lake were found to be in fair to poor condition; this may reflect the low water levels at the time of the study. The amount of summer trout habitat may not only impact on trout condition, but also a limiting factor to the trout fishery.

Although brown trout are present in the lake all year, anglers don't successfully target the species in the warmer months.

The lake is an important recreational fishery for the surrounding local communities. Nearly 70% of anglers interviewed for the angler surveys were from Wodonga, Albury or Lavington.

Redfin is the most popular species with Lake Hume anglers. These anglers are consumptive users of the resource and while such anglers generally support stocking and relaxed bag limits, support of any altered fisheries management arrangements will be influenced by perceived impacts to their redfin fishery.

In addition to the redfin fishery, the species currently stocked into Lake Hume provide increased opportunities, challenges and needs for anglers.

Anglers support the current range of species stocked into Lake Hume.

Introduction

The management responsibility for recreational fisheries in Lake Hume has been transferred from New South Wales Fisheries (NSW Fisheries) to Fisheries Victoria (FV). The lake contains a significant fishery; however, FV has little information on either its fish stocks or its anglers.

There has been a commitment by NSW Fisheries in the past, and FV recently, to stocking this water but there appears to be little information on the success or otherwise of these releases. As there will be considerable public scrutiny of FV's management of this water, the objective of this study is to provide information on angler use, fish population and catch details of this fishery.

It is essential that the best stocking options are established through management strategies based on sound information.

This project aims to benchmark the present status of the fishery including the fish stocks in the lake and the anglers who fish it.

Project Rationale

The project rationale included undertaking a comprehensive investigation of the Lake Hume fishery using both fishery dependant and fishery independent assessments.

A trial stocking of yearling brown and rainbow trout was also undertaken by FV during the course of this project. These fish were monitored using an angler creel survey so that the impact of the stocking could be assessed.

Objectives

The project involves a number of elements designed to gain information on the recreational fish populations of Lake Hume as well as angler use and catch details for the fishery as follows:

- Determination of the recreational fish species composition and population structure (length structure) for the lake

- Assessment of patterns of angler-use, fishing preferences and estimation of catch

- Evaluation of the success of trial stockings

- Development of a fish stocking and management strategy.

Methods

Benchmark current fishery

Netting surveys were undertaken in November 2004, April 2005, September 2005 and February 2006. Initially eighteen mesh nets were set overnight as six fleets of three nets. The fleets were a combination of three different sized mesh nets tied together. The eighteen nets were each 25 m long and included 3 x 52 mm, 3 x 89 mm, 3 x 102 mm, 3 x 114 mm and 6 x 152 mm mesh sizes (sizes in stretched mesh). Nets were set from a boat at right angles from the shoreline in the afternoon and pulled the following morning. Soak times were recorded. All fish caught were identified, weighed (nearest gram) and their total length measured (nearest millimetre). Nets were set on two consecutive nights.

Creel survey July 2005- June 2006.

Dividing a population into homogenous strata can reduce variance of an estimator of a population mean or total, and can increase precision and yield information at a range of levels and resolution (Pollock et al.1994). This means that by understanding when and where anglers fish in Lake Hume, a more precise creel survey design can be applied to the fishery.

Prior to the creel being designed, a pilot questionnaire was undertaken at the Golden Classic angling contest (2005) to investigate when Lake Hume anglers fish and whether stratification was possible. A sub-sample of anglers (n=25) was asked when and where they fished on Lake Hume.

Anglers used a variety of access points, not just official boat ramps, to access both arms of the lake. Many anglers fished the lake all year (50%) but others fished the lake in summer only (38%) or winter only (12%). Some anglers fished mainly weekends (48%) and/or holidays while others fished mainly midweek (24%). Some fished all through the week. More anglers fish in the morning or afternoon till dusk (37% morning, 37% afternoon) than in the middle of the day (20%).

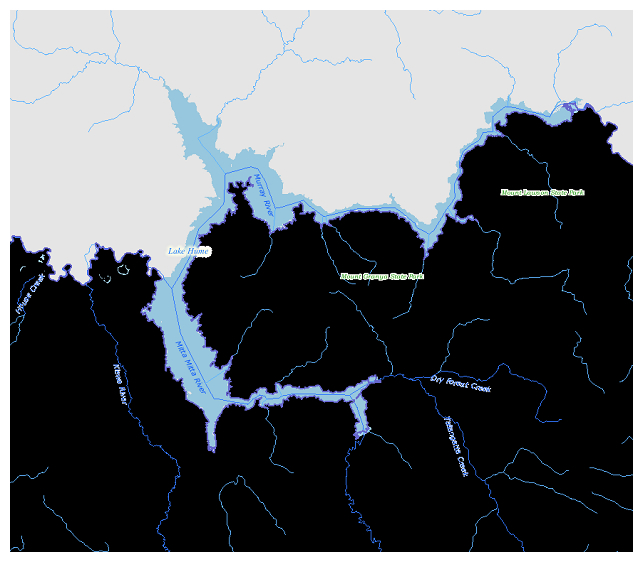

Based on the results of the pilot survey, a multi-strata design with unequal sub-sampling probabilities was adopted for the creel survey. The lake was divided into the two arms—the Murray River arm and the Mitta Mitta River arm—with the northern end of the dam wall as the delineation mark between the areas. Further strata included season (n=2, winter or summer), days of the week (n=2, weekdays or weekends, public holidays and school holidays) and finally times of day (n=3, morning (am) or midday (mid) or afternoon/evenings (pm)). For the purposes of the investigation, summer was from 1 October to 31 March and winter was from 1 April to 30 September. The morning creel sessions were from 7 am —11 am, the midday creel sessions were from 11 am—3 pm and the afternoon/evening creel sessions were from 3 pm—7 pm. Five survey session dates were randomly selected, without replacement, from each of the twelve possible substrata for each arm of the lake (Table 1).

The creel survey had a total of 120 survey sessions (60 in each lake arm) and each survey session lasted for 4 hours. The dates within each stratum, direction of travel and starting point for each creel session were randomly chosen before the survey commenced. Where possible, all anglers fishing within the randomly chosen lake arm were interviewed. Due to the relatively large size of the lake and the numerous access points, the creel survey used a boat based, roving design where the clerk travelled around the lake in a boat and anglers were intercepted whilst angling—or soon after they finished their fishing session. On busy days, every 3rd angler (or group of anglers) was interviewed to maximise angler contacts from the entire sample area strata within the time frame of the survey session. If every angler was interviewed, the creel clerk would only cover a smaller area of the lake; therefore, the results may not be representative of the whole sample strata.

Anglers were interviewed individually, even if they were part of a group or in the same boat.

Stocking of trout

The performance of these stocks was monitored through both the fishery independent assessment and the creel surveys. Fin clipping, prior to release as yearlings, allowed brown trout from the hatchery to be identified. Brown trout released in 2004 had their left ventral fin clipped; brown trout released in 2005 had their adipose fin clipped (Table 2).

Determination of angler typology

The level of angler specialisation of Lake Hume was assessed by interview and based on angling technique and fishing motivation (i.e. fishing for sport or for food). Anglers were asked about fish released and the reason for release. For this investigation, sport fishing was considered as a low consumptive use of the resource where anglers used specialised fishing gear, mainly low breaking strain lines (compared to the size of the fish being sought) and more 'technical' angling methods. Such methods could include fly, lure or bait. The emphasis is more on capturing rather than harvesting fish.

| Lake zone | Summer | Winter | ||||||||||

| Weekday (n=90) | Weekend/holiday (n=92) | Weekday (n=99) | Weekend/holiday (n=84) | |||||||||

| am | mid | pm | am | mid | pm | am | mid | pm | am | mid | pm | |

| Mitta Mitta arm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Murray arm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Table 1 Sampling frame and number of interview session for stratification of creel surveys of the Lake Hume during July 2005 - June 2006.

| Year | Number of stocked brown trout (fin clip) | Number of stocked native species |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 50 000 Murray Cod | |

| 2001 | 50 000 Murray Cod | |

| 2002 | 47 500 Murray Cod | |

| 2003 | 10 000 | 35 000 Golden perch |

| 2004 | 50 000 (Left Ventral) | 150 000 Golden perch |

| 2005 | 50 000 (Adipose) | 150 000 Golden perch |

| 2006 | 32 000 | 150 000 Golden perch |

| *10100 rainbow trout stocked 2006 | ||

Table 2 Government stocking history and fin clips in brackets for Lake Hume since 2000.

Results

Benchmark fishery

INDEPENDENT SURVEY

The Lake Hume fish fauna is dominated by introduced species. A total of 939 individual fish from six species was sampled from the four surveys. Carp (Cyprinus carpio) was the most abundant species accounting for nearly half the total number of fish caught (n=438, 47%). Other species included redfin (Perca fluviatilis) (n=243, 26%), golden perch (Macquaria ambigua) (n=162, 17%) brown trout (Salmo trutta) (n=44, 5%) goldfish (Carassius auratus) (n=23, 2%) carp-goldfish hybrids (n=21, 2%) and Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii) (n=5, 1%).

A total of 611 kg of fish were sampled from the four survey rounds, combined. Carp comprised over half (61%) of the total biomass sampled. In descending order of biomass contribution was golden perch (20%), redfin (11%), brown trout (4%), carp goldfish hybrids (2%), and then Murray cod and goldfish (both 1%)

Species summaries are presented in Table 3

Golden perch and Murray cod were the only native species sampled; both these species are stocked to maintain and enhance the recreational fishery in the lake.

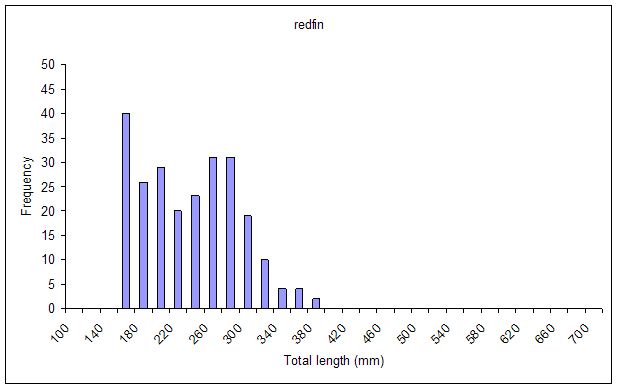

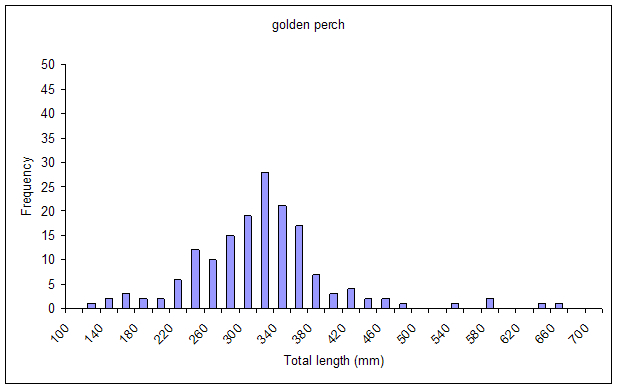

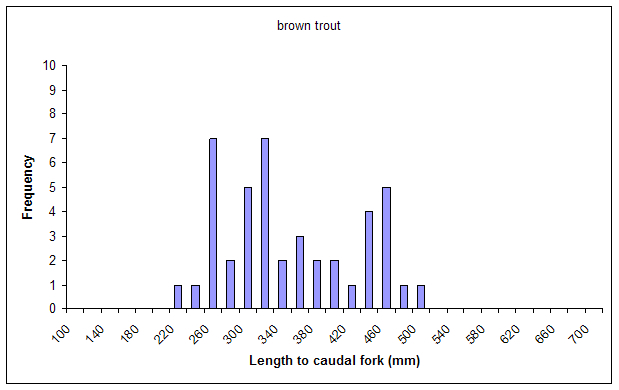

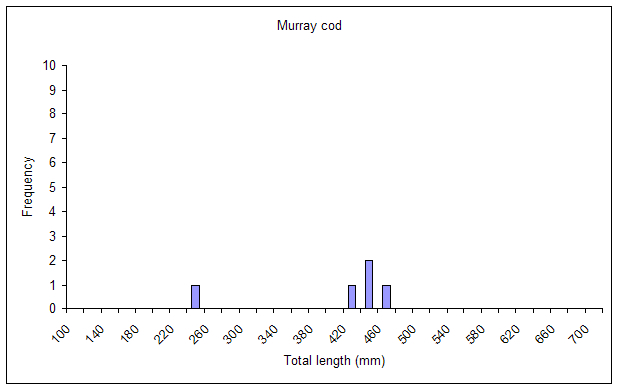

Length frequency charts are presented for redfin Figure 1), golden perch (Figure 2), brown trout (Figure 3) and Murray cod (Figure 4). These indicate the size ranges of fish in the lake.

| Species | Total number | Average length (mm) | Maximum length (mm) | Minimum length (mm) | Average weight (g) | Maximum weight (g) | Minimum weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carp | 438 | 342 | 560 | 122 | 891 | 2950 | 42 |

| Redfin | 243 | 243 | 395 | 160 | 284 | 1292 | 41 |

| Golden perch | 162 | 325 | 665 | 135 | 753 | 7335 | 46 |

| Brown trout | 44 | 357 | 5085 | 225 | 567 | 1740 | 130 |

| Goldfish | 23 | 211 | 285 | 130 | 229 | 488 | 57 |

| Murray cod | 5 | 408 | 475 | 240 | 1194 | 1638 | 223 |

| Carp-goldfish hybrids | 21 | 295 | 430 | 185 | 586 | 1352 | 117 |

Table 3 Summary of species captured from Lake Hume fishery independent surveys (all surveys combined).

| Area | Species | Total catch | se | Total kept | se | Total released | se | Total effort | se | Total cpue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murray Arm | Brown trout | 81 | 5 | 81 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 33699 | 343 | 0.002 |

| Carp | 458 | 23 | 458 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 33699 | 343 | 0.014 | |

| Golden perch | 171 | 12 | 171 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 33699 | 343 | 0.005 | |

| Redfin | 112175 | 2350 | 41302 | 782 | 70873 | 1628 | 33699 | 343 | 3.329 | |

| Mitta Mitta Arm | Brown trout | 396 | 21 | 296 | 15 | 100 | 9 | 29923 | 332 | 0.013 |

| Carp | 881 | 39 | 881 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 29923 | 332 | 0.029 | |

| Golden perch | 75 | 6 | 75 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 29923 | 332 | 0.002 | |

| Redfin | 42033 | 1029 | 15271 | 377 | 26762 | 810 | 29923 | 332 | 1.405 |

Table 4 Catch and effort estimates (with standard error) for both arms of Lake Hume from creel survey.

Figure 1 Length frequency of redfin caught in all fishery independent surveys (n=243).

Figure 2 Length frequency of golden perch caught in all fishery independent surveys (n=162).

Figure 3 Length frequency of brown trout caught in all fishery independent surveys (n=44).

Figure 4 Length frequency of Murray cod caught in all fishery independent surveys (n=5).

Benchmark catch and effort

Results from the creel survey for each arm of the lake are presented in Table 4. From July 2006 to June 2007, it was estimated that anglers fished for a total 63 622 hours and caught 154 208 redfin, 477 brown trout, 1339 carp and 246 golden perch. Of these, anglers released an estimated 97 635 redfin and 100 trout. Catch rates varied in each arm of the lake. Redfin catch rates were higher in the Murray River arm and brown trout catch rates were higher in the Mitta Mitta arm of the lake (Table 5).

| Lake Arm | Species | Catch per hour |

|---|---|---|

| Murray Arm | brown trout | 0.002 |

| carp | 0.014 | |

| golden perch | 0.005 | |

| redfin | 3.329 | |

| Mitta Mitta Arm | brown trout | 0.013 |

| carp | 0.029 | |

| golden perch | 0.002 | |

| redfin | 1.405 |

Table 5 Comparison of species catch per hour from each arm of Lake Hume.

Benchmark anglers

Boat based angling is more popular (75%) than shore-based angling. The majority of Lake Hume anglers are male (85%). Most anglers fish the lake at least monthly (81%) and only a relatively small group fish less than 3 times per month (19% of interviewed anglers) (Table 6). The principal target species of Lake Hume anglers is redfin then trout and golden perch (Table 7), although this can vary depending on the angler type (Table 8). Although Murray cod is present in the lake, the species was not specifically targeted by any interviewed angler.

Overall, Lake Hume anglers use a range of angling methods but specific methods were used for each target species. Bait fishing is mostly used by anglers targeting redfin, while trout anglers tend to use lures (Table 9). Golden perch anglers use both these methods (Table 9). Fly fishing is not a popular method in the lake, and although some people said they use the method in combination with other fishing styles, no angler nominated this as their primary angling method.

The majority of Lake Hume anglers target redfin (Table 7) but the angling techniques used for this species generally remain unspecialised (i.e. bait) (Table 9). Based on the fishing methods and target species, angler typology for Lake Hume is dominated by "species specialists". There is a trend where the more often an angler fishes the lake, the less they target 'anything' and the more they target redfin (Table 8).

| Frequency of fishing trips | Percentage |

|---|---|

| ›3 per month (Active) | 62 |

| 1-3 per month (Regular) | 20 |

| ‹3 per month (Occasional) | 19 |

Table 6 Percentage of anglers per frequency of fishing trips (angler type).

| Species | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Redfin | 65 |

| Trout | 20 |

| Golden perch | 6 |

| Carp | 1 |

| Murray cod | 0 |

| Anything | 7 |

Table 7 Percentage of anglers who target main species.

| Species | Occasional | Regular | Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redfin | 59 | 61 | 70 |

| Trout | 15 | 24 | 20 |

| Golden perch | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Carp | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Anything | 19 | 8 | 3 |

Table 8 Percentage of target species by angler type.

| Species | Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bait | Lure | Fly | |

| Redfin | 72 | 15 | 0 |

| Trout | 13 | 78 | 0 |

| Golden perch | 50 | 34 | 0 |

Table 9 Percentage of principal methods used to target main species (anglers who use a combination of methods not included).

In general, the more specialised an angler becomes, the less important fishing for food and the more important fishing for sport (Bryan 1927). However, in Lake Hume the redfin anglers mostly keep the fish they catch and, in this regard, are not typical of an angling specialist.

Anglers were asked to rate their catch in terms of acceptability. Responses indicated most anglers were not satisfied with their fishing. Redfin and trout were the only species that provided acceptable (OK) or better catch rates from the Lake Hume fishery (Table 10). Redfin were the only species that provided some anglers with higher than acceptable catch rates (Table 10).

Lake Hume anglers had a range of ages but the largest percentage was in the 50-69 years of age bracket (Table 11). The lake is popular with local anglers. Residents from Albury, Lavington and Wodonga postcodes comprised 69.41% of the interviewed anglers.

The proportion of anglers interviewed coming from various postcodes is presented in Table 12.

| Target species | Dead | Slow | OK | Fast | Best ever |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redfin | 28 | 32 | 28 | 10 | 2 |

| Trout | 67 | 14 | 18 | ||

| Golden perch | 80 | 20 | |||

| Carp | 100 | ||||

| Anything | 67 | 17 | 17 |

Table 10 Principal target species and percentage of anglers who reported acceptable catch rates

| Age Bracket | % of anglers |

|---|---|

| ‹17 | 8 |

| 18-29 | 13 |

| 30-44 | 19 |

| 45-49 | 17 |

| 50-69 | 32 |

| ›70 | 10 |

Table 11 Percentage of interviewed anglers per age bracket

Trial Stocking of trout

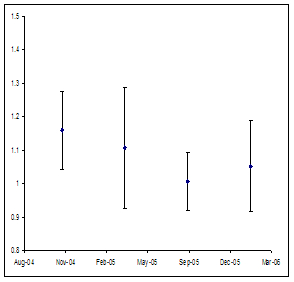

Stocked brown trout comprised 22% of the trout sampled from the Lake Hume fishery independent surveys and 16% of the brown trout in anglers catches seen by creel clerks. The stockings seem to have had little impact on the overall trout fishery. Of the estimated 477 brown trout caught in the year, stocking contributed about 75 extra fish. A total of 50 000 brown trout were stocked into the lake in 2004; return to anglers from this stocking was estimated at 0.15%. No fin-clipped fish from other release years were sampled. The dominance of unclipped trout in the sample indicates that non-hatchery stock is present in the fishery. The origin of the non clipped fish is not known—they could be from natural recruitment events or from the 2003 stocking. The sampled brown trout were generally thin and in poor condition overall. The condition factor of brown trout varied across the project sampling timeframe but was not significantly different (p>0.005) between sampling trips. The condition of the trout ranged from poor to fair where condition factor of 0.0~1.1 is poor, 1.1~1.30 fair and 1.3~1.5 good (Barnham and Baxter 1998).

Figure 5 Mean condition factor of Lake Hume brown trout from each survey round (error bars are ±1 standard error).

| Residential postcode location | % of recorded postcodes |

|---|---|

| WODONGA | 33.64% |

| ALBURY | 24.09% |

| LAVINGTON | 11.69% |

| ALLANS FLAT | 5.08% |

| MULLINS | 3.86% |

| BROCKLESBY | 1.63% |

| BALLDALE | 1.32% |

| BENNISON | 1.22% |

| APPIN PARK | 1.22% |

| Unknown | 1.12% |

| HOWLONG | 1.02% |

| BARNAWARTHA | 0.81% |

| ASHMONT | 0.81% |

| ENDEAVOUR HILLS | 0.61% |

| HENTY | 0.51% |

| CHILTERN | 0.51% |

| BUNDALONG | 0.51% |

| BOGONG | 0.51% |

| ALBANVALE | 0.41% |

| WANGARATTA | 0.30% |

| FAWKNER | 0.30% |

| COLDSTREAM | 0.30% |

| BUNDALAGUAH | 0.30% |

| BRUARONG | 0.30% |

| BOORHAMAN | 0.30% |

| BENARCH | 0.30% |

| BAARMUTHA | 0.30% |

| ALPHINGTON | 0.30% |

| WAHGUNYAH | 0.20% |

| TEMPLESTOWE HEIGHTS | 0.20% |

| LANCEFIELD | 0.20% |

| LAKE ROWAN | 0.20% |

| KAPOOKA | 0.20% |

| GREENDALE | 0.20% |

| FRENCH PARK | 0.20% |

| DERRIMUT | 0.20% |

| COBURG | 0.20% |

| BUFFALO RIVER | 0.20% |

| BROOKSIDE CENTRE | 0.20% |

| BOORHAMAN NORTH | 0.20% |

| BONEGILLA MILPO | 0.20% |

| BIGGARA | 0.20% |

| BAYSWATER | 0.20% |

| BAROOGA | 0.20% |

| BANGHOLME | 0.20% |

| ARDMONA | 0.20% |

| ALLANSON | 0.20% |

| WALLA WALLA | 0.10% |

| URANA | 0.10% |

| TAWONGA SOUTH | 0.10% |

| STRATHMERTON | 0.10% |

| ROWLAND FLAT | 0.10% |

| PAKENHAM | 0.10% |

| MOORINA | 0.10% |

| LEICHHARDT | 0.10% |

| LAUREL HILL | 0.10% |

| KATUNGA | 0.10% |

| HEATHCOTE JUNCTION | 0.10 |

| FOREST HILL | 0.10% |

| ELSTERNWICK | 0.10% |

| CURRIE | 0.10% |

| CRAIGIEBURN | 0.10% |

| COROBIMILLA | 0.10% |

| COBRAM | 0.10% |

| CHELTENHAM | 0.10% |

| CHARLEROI | 0.10% |

| CAULFIELD JUNCTION | 0.10% |

| CAMPSIE | 0.10% |

| BUNNALOO | 0.10% |

| BULLENGAROOK | 0.10% |

| BOWNA | 0.10% |

| BOORAL | 0.10% |

| BARTON | 0.10% |

| BAMARANG | 0.10% |

| ACACIA PARK | 0.10% |

Table 12 Percentage of home residential postcodes as reported by Lake Hume anglers

Discussion

General Fishery

Lake Hume is very popular with local Albury Wodonga anglers. The lake supports a redfin fishery and although it has been stocked with native species including golden perch, Murray cod and trout, the native stocked species are rarely targeted and the trout only seasonally. The majority of the recreational fishers interviewed came from the districts surrounding the lake (Table 12) and fish it more than once per month (Table 6). It must be noted that the higher numbers of regular anglers compared to occasional anglers is likely to include some avidity bias. Avidity bias occurs where the more avid participants are more likely to be encountered onsite. This means that avid anglers are overly represented in the study. The extent of avidity bias in this study could not be determined as anglers were not asked if they had been previously interviewed. Many Lake Hume anglers are in the older age categories and the fishery forms an integral part of their recreation (Table 11). Lake Hume is predominately a boat based fishery.

REDFIN

Redfin was the most targeted fish in the lake and the most abundant in the catch. (Table 7)

Redfin is the most popular freshwater angling species in Victoria (Henry and Lyle 2003). Redfin are popular because they are easy to catch (often in large numbers) and are highly regarded as a table fish.

Redfin anglers in Lake Hume primarily use bait and tend to fish with relatively unsophisticated gear compared to other specialist anglers such as fly fishers (Table 9). Redfin anglers are considered to be consumptive users of the resource; they take most of the fish they catch for food rather than releasing for sport. In general, the only redfin that are returned to the water are either considered too small for eating or the angler is high grading smaller fish with larger fish in order to keep within bag limits. Anglers were observed on several occasions with catches in excess of the bag limit (unpublished observation).

Redfin do not exhibit the fighting qualities to be seriously considered as a sportfishing species. Whilst some anglers may argue that they fish for sport, the fishing gear and methods used by these anglers is no different to the non-sporting motivated anglers. The fact that larger fish are seldom returned to the water is also consistent with anglers taking fish for consumption.

GOLDEN PERCH

Golden perch are stocked into the lake periodically. Golden perch in Lake Hume grow to a relatively large size, some even nearly up to 700 mm in length (Figure 2). Comparatively few Lake Hume anglers specifically target them due in part to inconsistent catches and the disputed eating qualities of the species. It is generally considered that the eating qualities of golden perch vary depending on the size of the fish and where the fish was caught (Anon 2007). Anglers who target golden perch may do so more for sport than for food or because they are opportunists who take advantage of a seasonal peak in fish activity levels - 'hot bite'. Anecdotal information suggests that golden perch are mostly taken in Lake Hume for a short period in spring when they can be caught near the banks. This phenomenon is similar to the golden perch fishery in Lake Eildon, where golden perch are closer to the shore in spring (then move away from the shore as summer progresses) (Douglas, unpublished information). The Lake Hume golden perch fishery is under-utilised at present.

MURRAY COD

Murray cod are stocked into the lake but they are seldom specifically targeted. Fishery independent surveys (Table 3) indicate the presence of Murray cod in Lake Hume but in low abundance compared to other species. Murray cod were not targeted by any of the anglers interviewed. This may be due to the relatively low densities of fish and the more specialised methods required to effectively target this species. Anglers who decide to target Murray cod may use methods (baits and lures) that preclude the by-catch of other species in the lake and thus return low catch rates. Satisfaction of the sport fishing experience is dependant on the fulfilment of the incentives that inspire a person to go fishing for a particular species (Calvert 2002). Therefore, if their expectations are not met with cod captures after some effort, then they may lose enthusiasm to continue. If the fishery is unreliable or very slow, then fewer anglers are likely to pursue the target species. At present targeting Murray cod in Lake Hume is probably in the realm of the more specialist angler who is looking for a challenge. It may be some time before more anglers target the species. Murray cod were stocked into Lake Eildon for many years before there were enough large fish to attract anglers to target the species.

TROUT

Trout are stocked in the lake annually. The trout fishery in Lake Hume is mostly boat based and involves lures and trolling (Table 9). Participation in the trout fishery is seasonal and linked to angler perceptions of surface water temperatures. The Lake Hume 'season' starts in autumn, continues through winter and spring, and ends when surface waters increase (and redfin catch rates increase). Netting surveys indicate that trout are present in the lake all year but were only sampled in the deeper water near the wall in summer. It is likely that trout inhabit deeper water in summer when stratification by temperature is common (Douglas et al. in press). These fish could be targeted by recreational anglers all year if they used specialist trolling methods (such as down rigging).

BROWN TROUT STOCKING

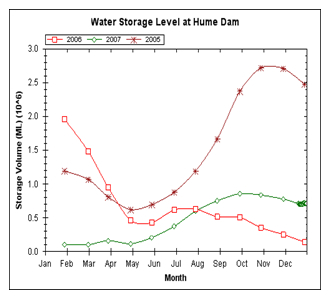

Brown trout stocked contributed 16% of the catch which equates to an extra 75 fish in anglers' catches during 2005–2006. This equated to ‹1% of the fish stocked. Natural recruitment and suitable habitat conditions in the lake are the main drivers of maintaining a trout fishery in Lake Hume. The trout population in the lake is dependant on the extent of suitable habitat. Water levels in Lake Hume decreased rapidly to relatively low levels in the summer (Figure 6); this may have impacted on summer trout habitat and the ability of the lake to support a large trout population.

In stratified impoundments and lakes, trout habitat can be squeezed in summer between high water temperatures extending from the surface and low oxygen levels in the lower water column. Water temperature tolerance ranges of fish are species-specific and brown trout are stenothermal (narrow thermal range) (Ficke et al. 2007) and are sensitive to water temperature changes. In a review of the impacts of global warming, Ficke et al. (2007) explained how water temperature impacts on trout:

"Trout can thermoregulate by selecting thermally heterogeneous microhabitats, but they are constrained by the range of temperatures available in the environment. Because biochemical reaction rates vary as a function of body temperature, all aspects of an individual fish's physiology, including growth, reproduction, and activity are directly influenced by changes in temperature. Therefore, increasing [global] temperatures can affect individual fish by altering physiological functions such as thermal tolerance, growth, metabolism, food consumption, reproductive success, and the ability to maintain internal homeostasis in the face of a variable external environment"

Habitat squeezing also has implications for trout density, mortality, and lake carrying capacity (Rowe and Chisnall 1995). When trout habitat is in short supply, a bottleneck results and can cause density dependant mortality levels to rise (Reeves et al. 1989). In impoundments, the habitat reduction can be dramatic in summer. It was estimated that in Lake Eildon, trout habitat was reduced by 70% over summer (Douglas et al. in press). Lake Hume is shallower than Lake Eildon (Lake Hume 41.4 metres deep; Lake Eildon 76 metres deep), and consequently, the impact of habitat squeeze in Lake Hume is expected to be greater. The impact of the habitat squeeze is also exacerbated by low water storage levels. Habitat squeeze is greater when the lake is shallower (or lower) as the warm summer water can extend all the way to the lake bed over much of the lake. At the time of the summer sampling, Lake Hume reached exceedingly low storage levels (under 16%) (Figure 6).

The low numbers of trout returned in both the recreational catch and the fishery independent surveys suggests that the trout population was not large. Because trout were only captured near the weir wall in the warmer months, it is possible that in summer, trout habitat may be restricted by the warm surface water temperature and limited to a small area of deeper water near the weir wall. The status of the Lake Hume trout population may therefore be dependant on the amount of summer trout habitat. Modelling predictions of the amount of summer trout habitat at a range of storage volumes may be a useful tool to predict the likelihood of wild-stock, or stocking success (Douglas et al. in press).

Figure 6 Water levels in Lake Hume in 2005, 2006 and 2007 (Chart sourced from Goulburn Murray Water website).

Lake Hume angler typology and Fisheries Management

ANGLER TYPOLOGY

Segmenting anglers by their recreational specialisation has been used as a method to explore differences in terms of angler preferences, motivations, and attitudes (Chipman and Helfrich 1988, Hahn 1991, Scott and Schafer 2001, Kuentzel and Heberlein 2006, Oh and Ditton 2006). Awareness of the various angler typologies (or sub-groups) can enhance understanding angler attitudes and thus aid fishery management.

ANGLER SPECIALIZATION

Classification of anglers by catch preference, experience and participation can help fishery managers understand diversity in preferences and attitudes among recreational anglers (Fisher 1997). Numerous descriptive studies examining the motives, attitudes, and behaviour of anglers have been conducted that confirm the non-existence of the 'average' angler and highlight significant diversity among anglers and in their activities (Loomis and Ditton 1987). Despite these differences, anglers' motivations, attitudes and values seem to cluster according to the degree of angler specialisation (Bryan 1927). As anglers become more experienced in their sport, their level of species and gear specialisation increases on a continuum of behaviour from the general to the particular, where anglers range from those having a general interest in the sport to others who specialise in both species and techniques. Bryan (1979) reported that these 'specialist' groups tend to view fisheries and fisheries management in different but predictable ways.

In the present study, anglers fishing for 'sport' were considered to be further along the 'continuum of behaviour' and thus more specialised than those fishing for food. The Lake Hume fishery is dominated by species specific anglers who concentrate their angling effort on redfin (Table 4 and Table 7). The majority of Lake Hume anglers principally target redfin although some will occasionally switch to trout when the trout are fishing well (Table 7). Some golden perch specialists were identified but they did not make up a significant part of the angling population as they only fished the Lake for a short period. No Murray cod or trout only specialists were identified.

ANGLER SPECIALIZATION AND FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

Integrating specialisation theory into angler studies can help explain important attitude differences that may be present among diverse recreation users (Salz and Loomis 2005). Innovative polices to manage resource users should be based on sound biological principles as well as on sound social science theory; therefore, policies require both information on an inventory of available resources and on levels of angler specialisation (Hahn 1990).

The classification of anglers based on their qualitative and quantitative consumption of the resource (i.e. sport or food angling) gives insights into how the different groups are likely to respond to various policy changes, particularly any changes related to a reduction in permissible catch (decreased catch limits or increased minimum takeable sizes) or, in the case of Lake Hume, any management actions that may impact on the performance of the redfin fishery.

Bryan (1997) classified trout anglers into four groups based on their level of specialisation and found that the groups tended to have specific values and attitudes. The groups include novices, generalists, specialist and technical specialists. There was a lack of anglers who fall into Bryan's technical specialist category in Lake Hume. The trout anglers who fish the lake tend to use trolling methods and often fish for other species (redfin). They are, therefore, classified as generalists. Trout trollers were most likely to be using unsophisticated gear and methods (flat line trolling) rather than the more sophisticated down rigging techniques. Trolling can be highly specialised with considerable gear requirements (down riggers) but few of these angler types were seen on Lake Hume during the creel. Other specialised trout fishing methods such as fly fishing were also not seen used in the Lake Hume trout fishery. Why specialists do not fish Lake Hume may be symptomatic of the trout returns and therefore be dependant on current water conditions and the associated state of the trout stocks. Specialist trout anglers are prepared to travel some distance to enjoy their sport and thus may target other waters where their angling returns are expected to be higher (Hann 1991). The lack of these more specialised methods seen in Lake Hume adds further support to the notion that the anglers who fished for trout in the Hume in the creel survey period are generalists.

Specialised sport-only anglers are under-represented in the Lake Hume fishery. The change to angling specialist depends on the angler's motivation for fishing—if an angler can regularly catch fish and do not need any for the table, they may start to try and catch fish in a more challenging or technical way. The degree of specialisation in angling is dependant to some degree on the angling qualities of the species being sought. In the case of redfin, the relative ease of capture of the species means that high level specialisation is not required to catch the fish and anglers with limited experience can catch the enough fish to meet their satisfactions. For many anglers, this is as far as they want or need to go on their angling journey. Although the attributes of the species don't necessarily require specialisation, sophisticated approaches, as used on other species, could still possibly be applied to redfin. For example, the use of similar techniques and gear—such as soft plastic—to those used in bass or bream fishing tournaments in Australia or finesse techniques used for numerous recreational fisheries throughout the world, seems underutilised at present in redfin fisheries such as Lake Hume.

REDFIN SPECIALISTS

The redfin specialists are competent anglers who principally fish for food and thus are consumptive users of the fishery resource. This finding has implications for managers because such users tend to favour management interventions that they feel provide more of the resource to anglers, such as stocking, and disagree with restrictive arrangements such as bag limits. Mid and high consuming groups tend to oppose angling restrictions to a higher degree than sport fishing anglers (Aas and Kaltenborn 1995). Specialists who are generally less intense users of the resource tend to support fisheries interventions that limit catches, such as gear restrictions and catch and size limits—that may enhance a fishery (Hahn 1991, Aas and Kaltenborn 1995, Oh and Ditton 2006).

ANGLER MOTIVATION AND SATISFACTION

Angling experiences consist of at least three dimensions and include motivation, behaviour and satisfaction. These dimensions are important aspect of recreational fishing and the subject is well covered by Calvert (2002) Schramm and Gerard (2004), Decker et al. (1980), and Hahn (1991). Motivations and satisfaction will vary depending on the typology of the angler.

Satisfaction can vary depending on the specialisation level of the angler. The less specialised an angler, the less the angler's satisfaction is connected to the resource. There are more substitutable experiences available to them than to the more specialised, resource specific angler (Hahn 1991). As an example, catching a fish, regardless of species, may be enough to satisfy the less specialised angler. But the more specialised angler will only be satisfied with catching their specific target species. Lake Hume redfin anglers are generally satisfied because the lake produces catches of their favoured angling target species.

Non-specialised and novice anglers probably lack the skills to consistently catch any fish from Lake Hume and they are likely to see angling as luck. Their satisfaction rating is low and the capture of any fish species would likely make them satisfied.

Angler satisfaction is influenced by completed experience results from both motivations and behaviours and influences future motivations to go fishing (Calvert 2002). Angler satisfaction is often overlooked in fishery management; satisfaction of the angler's motivational needs contributes towards the success of a fishery. The degree that a fishery can satisfy the varied views and motivations of the range of anglers who utilise it could be viewed as a measure of the fisheries success. A truly successful fishery would be one that satisfies the complete range of desired angler experiences.

Catch rates are often used as a surrogate of angler satisfaction but are not the most reliable measure of a fishery's ability to satisfy anglers because a range of catch and non-catch related motivations lead toward satisfying angler's expectations and their angling experience (Calvert 2002).

DEVELOPMENT OF A FISH STOCKING AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGY FOR LAKE HUME

In Lake Hume the important angling typology is the redfin fisher who focuses not only on catching fish, but also on harvest. These anglers are still highly consumptive of the resource. Management actions that increase fish stocks, such as fish stocking would probably be supported by them, while restrictive actions that limit levels of take will most likely be opposed (Hahn 1991, Aas and Kaltenborn 1995, Oh and Ditton 2006). These Lake Hume anglers would assess any fisheries management actions by how such actions would affect (perceived or proven) their redfin fishing. For example stocking a possibly redfin-competitor or redfin-predator species would probably not be supported as much as stocking a non-competitive species.

At present an alternative species to redfin is not available to the Lake Hume angler. Golden perch are inconsistent in capture and have debatable eating qualities (can get fatty). Murray cod require the anglers to specialise and require much effort between captures. Silver perch have been trialled in the lake but were not successful. Large specimens of silver perch in other impoundments are very hard to catch. Translocation policy restricts the stocking of fish outside their natural range so no 'new' species can be stocked. Trout are acceptable and desirable from a section of the Lake Hume fishing fraternity but despite enthusiastic stocking, the trout fishery in the Lake remains inconsistent.

The inconsistency of golden perch is somewhat of a problem to establish the species in Lake Hume (and other impoundments) but this may be a commitment issue. Lake Eildon is an example of a golden perch fishery that is only developing after many years of consistent stocking. The netting results from Lake Hume indicate the species is present but anglers do not target the fish all year. The presence of golden perch (and Murray cod) in the storage provides the element of a challenge to so-motivated anglers or represents a welcome by-catch by other anglers. These native species provide a valuable addition to the Lake Hume fishery. Lake Eildon fishery is only recently beginning to improve but this has come after many years of stocking. Perhaps the Lake Hume golden perch fishery will follow a similar path if the commitment to continue stocking remains.

The current suite of stocked species provides a variety of species and caters for a wide range of angling abilities and styles. Such a strategy also conforms to the objectives of the NEFMP. However, there is a need for adaptive management arrangements to be considered for the fishery as conditions and water levels are constantly changing and impact on the fishery.

Conclusions

The project involved a number of elements designed to gain information on the recreational fish populations of Lake Hume as well as angler use and catch details for the fishery as follows:

- Determination of the recreational fish species composition and population structure (length structure) for the lake

- Assessment of patterns of angler-use, fishing preferences and estimation of catch

- Evaluation of the success of trial stockings

- Development of a fish stocking and management strategy.

The lake is an important recreational fishery to Albury/Wodonga residents and the surrounding local communities.

The importance of redfin to the Lake Hume fishery creates scope to manage the species as the principal fishery. There is no formal management of redfin except for a catch limit. Information of redfin biology and behaviour in Lake Hume would assist managers to explore possibilities regarding specific redfin management and help anglers target the species more effectively.

The golden perch fishery has not been consistent but is currently under utilised. From a fisheries management point of view, further investigations into what is needed to produce a relatively consistent golden perch fishery may offer insights into how best to stock the species.

Trout stocking in the lake is continuing. Lake levels and the reduction of summer habitat are probably affecting the success of trout stocking. Setting a trigger point of anticipated annual lake height for suspending trout stocking could be considered. Alternatively, the predicted size of the summer habitat could be used to modify the number of trout introduced.

Acknowledgements

Cameron McGregor undertook the bulk of the creel interviews, but others including Matt McMahon, Greg Sharp, Daniel Stoessel, and Russel Strongman also assisted. Russell Strongman with Matt and Greg completed the fishery independent surveys. Kylie Hall, Paul Brown, Wayne Fulton, Taylor Hunt and James Andrews commented on the manuscript.

This project is funded by the Victorian Government using Recreational Fishing Licence Fees.

References

Aas Ø. and Kaltenborn BP (1995) Consumptive orientation of anglers in Engerdal, Norway. Environmental Management Volume 19, Number 5: 751–761

Anon (2007) Golden perch information from website http://www.sweetwaterfishing.com.au/GoldenPerch.htm

Barnham, C and Baxter A (1998). Condition factor, k, for salmonid fish. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources–Fisheries Branch.

Bryan H (1979). Conflict in the great outdoors. University of Alabama Bureau of Public Administration, Sociological Studies 4 , Tuscaloosa. In Hahn J (1991) Angler specialisation: Measurement of a key sociological concept and implications for fisheries management decisions. American Fisheries Society Symposium 12: 380–389.

Bryan H (2000) Recreation specialisation revisited. Journal of Leisure Research Vol 32, No1: 18–21.

Calvert B (2002) The importance of angler motivations in sport fishery management. In Pitcher, T.J. and Hollingworth, C.E. (Eds.) Recreational fisheries: ecological, economic and social evaluation. Fish and Aquatic Resources Series, 8.

Chipman, BD and Helfrich LA (1988) Recreational specializations and motivations of Virginia River anglers.North American Journal of Fisheries Management, Vol 8, No 4: 390–398.

Decker, DJ Brown TL and Gutiérre RJ (1980) Further insights into the multiple–satisfactions approach for hunter management. The Wildlife Society Bulletin Vol 8, No. 4, Winter.

Douglas, JW (2009) Movement and habitat preference of golden perch in Lake Eildon. Fisheries Victoria Report Series. Department of Primary Industries, Victoria.

Douglas, J, Abery N, Hunt, T and Allen, M (in press). Fish habitat in lakes can be quantified using GIS modelling. Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management.

Ficke AD, Myrick CA and Hansen LJ (2007) Potential impacts of global climate change on Freshwater Fisheries. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, vol 17 no.4.

Fisher, MR (1997) Segmentation of the Angler Population by Catch Preference, Participation, and Experience: A Management–Oriented Allocation of Recreation Specialization. North American Journal of Fisheries Management. Vol 17, No. 1: 1–10.

Hall K (2002) Lake Mokoan Fishery Assessment. Freshwater Fisheries Report No 02/1, Natural Resources and Environment.

Henry, GW and Lyle, JM, (2003). The National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey. Final Report to the Fisheries Research & Development Corporation and the Fisheries Action Program. Project No. 1999/158. NSW Fisheries Final Report Series No. 48. ISSN 1440–3544. 188.

Kuentzel WF and Heberlein TA (2006) From novice to expert? A panel study of specialization progression and change. Journal of Leisure Research, Vol. 38, No. 4: 496–512.

Loomis DK and Ditton RB (1987) Analysis of motive and participation differences between saltwater sport and tournament fishermen. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, Vol 7 No. 4: 482–487.

North East Fishery Management Plan (2007) Fisheries Victoria Management Report Series No. 48

Oh C and Ditton R (2006) Using recreation specialization to understand multi–attribute management preferences. Leisure Sciences, Vol 28, No. 4: . 369–384.

Pollock, KH, Jones CM, and Brown TL (1994) Angler survey methods and their applications in fisheries management. American Fisheries Society Special Publication 25. 371.

Reeves GH, Everest FH and Nickelson TE (1989). Identification of physical habitats limiting the production of coho salmon in western Oregon and Washington. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report. PNW–GTR–245.

Rowe, DK and Chisnall BL (1995) Effects of oxygen, temperature and light gradients on the vertical distribution of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, in two North Island, New Zealand, lakes differing in trophic status. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 1995, Vol. 29: 421–434.

Salz RJ and Loomis DK (2005) Recreation Specialization and Anglers' Attitudes Towards Restricted Fishing Areas. Human Dimensions of Wildlife Vol 10, No. 3: 187–199.

Schramm HL Jr, and Gerard P D (2004). Temporal changes in fishing motivation among fishing club anglers in the United States. Fisheries Management and Ecology Vol 11 No 5: 313–321.

Scott D and Scott Shafer C (2001) Recreational specialization: A critical look at the construct. Journal of Leisure Vol 33 No. 3: 319–343.

Appendix 1

Interview Sheet

| Lake Hume Recreational Fishing Survey | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Fisheries Management Questions Refer: Rob Gribb 03 9412 5701 | ||||||||||||

| Specific Research Project Questions Refer: Wayne Fulton 03 5770 8016 | ||||||||||||

| Recreational Fishing Survey LAKE HUME | Interviewer: ______________ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date: __/__/____ Page __ of __ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Angler No. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interview time | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Estimated finish time? (Y/N) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number in party? Alone? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Target species? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Species caught (Sp. Code 1 / Sp. Code 2) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number caught (#Sp. 1 / #Sp. 2) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Species returned (Sp. Code 1 / Sp. Code 2) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number returned (#Sp. 1 / #Sp. 2) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Finclip/s? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reason for release? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main method? F = Fly B = Bait L = Lure |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boat / Bank or Both? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Angler type? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How often do you fish hume? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What season/s? (circle) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Satis. level: How do you ratethe fishing at Lake Hume today? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On this visit to Lake Hume, what other waters have you fished? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you fish Lake Hume during the Rivers closed-season? (Yes/No) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aware of Victorian regulations re Lake Hume? |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gender (M/F) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age bracket |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postcode | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species: BT Brown trout, RT Rainbow trout, TR Unspecif. trout, AS Atlantic salmon, RF Redfin, CC Common carp, Bf Blackfish, MC Murray cod, GP Golden perch, SP Silver perch

Reason for release: S Surplus to requirement, U Undersized,, SP Sport only, T Tagged fish, CL Catch limit

Angler type: O Occasional < 1 x trips month, R Regular 1-3 x trips a month, A Active > 3 x trips a month

Satisfaction level: B Best ever, F Fast, O OK, S Slow, D Dead

Age bracket: A 17 or younger, B 18-29, C 30-44, D 45-49, E 50-69, F 70 or older

| Lake Hume Recreational Fishing Survey: Retained Catch | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date: __/__/____ | ||||

| Angler No. | Species | Finclip | Fork Length (cm) | Was this fish caught within 100m of interview location? (Y/N) |