Increasing knowledge of Victoria’s growing recreational yellowtail kingfish fishery

Executive summary

Executive summary

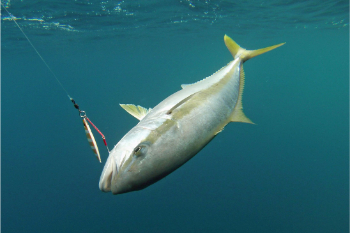

Prior to the early 1990’s, yellowtail kingfish (Seriola lalandi) were commonly caught by recreational anglers at various offshore locations across Victoria (VIC), primarily in the warmer months. While the historic abundance of yellowtail kingfish in VIC waters was not as high as in New South Wales (NSW) waters, the fish were often very large (up to 30+ kg), particularly around the entrance to Port Phillip Bay (‘The Rip’). During the mid-1990’s both the number and size of yellowtail kingfish taken by recreational anglers in VIC waters decreased dramatically. This was also observed in the commercial sector where 2–12 tonnes were landed between 1980 and 1993, which then dramatically dropped to <1 tonne per year for almost two decades. Consequently, interest in targeting yellowtail kingfish declined. The low availability of yellowtail kingfish to VIC anglers continued until about 2010 when exceptional yellowtail kingfish catches during summer and autumn were reported. It is clear from the resurgence of targeted recreational fishing that their availability has increased considerably over the last decade.

The reasons for the recent increased availability are unclear, and it is a shared goal for managers and anglers alike, that the current great fishing for yellowtail kingfish in VIC waters is sustained for the long-term. Uncertainties included a limited knowledge of:

- yellowtail kingfish stock structure around southern and eastern Australia,

- migratory dynamics and residency behaviour of yellowtail kingfish in VIC waters,

- length and age composition and basic biological characteristics (growth, reproduction) of yellowtail kingfish occurring in VIC waters.

This project aimed to apply multiple approaches to improve understanding of the yellowtail kingfish fishery in VIC including; genetics, biological sampling, otolith chemistry and a trial of satellite tags. Additional components of the study included a review of historical records of recreationally caught yellowtail kingfish and the potential for marine stocking of the species in VIC waters.

Results from the genetic component of this study confirmed a separate genetic stock of yellowtail kingfish in WA and supported a single stock hypothesis across eastern and south-eastern Australian waters. However, limited sample numbers were available from NSW, and SA was not included in the sampling program. Minor regional genetic variation was detected using the most powerful genetic methods; microsatellites and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). A properly structured and resourced genetics study using SNPs is recommended to provide definitive conclusions on population structure around southern and eastern Australia, and importantly to identify likely reproductive sources of yellowtail kingfish found in VIC waters.

Growth rates and length/age at maturity for yellowtail kingfish in VIC were generally consistent with studies from NSW. Length/age compositions of recreationally caught fish in VIC varied between the eastern, central and western regions of the State, with greater proportions of larger/older fish present in eastern and western VIC waters. However, across all three regions most fish were less than 100 cm total length, less than 6 years of age, and immature. No evidence of spawning fish was found, although females with developed gonads were observed. The dominance of smaller fish in the contemporary fishery is not consistent with the historical records and anecdotally fish greater than 100 cm and 10+ kg were very common prior to the early 1990’s. The current fishery is likely to be in a recovery phase driven by improved management, reduced harvest and higher recruitment over the last decade, and it therefore likely that high fishing mortality (particularly of juvenile yellowtail kingfish in NSW), and sustained poor recruitment likely influenced the decline of yellowtail kingfish in VIC in the early 1990’s rather than an abrupt change in their migratory patterns or habitat preference.

One yellowtail kingfish in this study was successfully tagged with a satellite tag. The fish moved from near Portland in western VIC, east through Bass Strait to near Flinders Island, over a 69-day period from April–June 2017. Unfortunately, two other tag releases failed, due to a combination of equipment failure and possible seal predation. Satellite tags can be deployed successfully on yellowtail kingfish, but they are expensive, and exploration of acoustic tagging is recommended to further explore migration patterns, taking advantage of the Integrated Marine Observing System receiver network around southern Australia.

A trial of otolith stable isotopes in this study, in particular the oxygen isotope ratio (18O/16O) supported the application of this technique to expanded studies of thermal history and population structure. The results supported the hypothesis that VIC yellowtail kingfish start their lives in warmer waters outside of VIC, most likely along the eastern seaboard off NSW, but spend more time in cooler waters as they get older. This is consistent with a model of seasonal migration between NSW and VIC and habitat suitability.

Finally, a review of stocking potential indicated that hatchery production of yellowtail kingfish is well established in Australia. However, due to the temperature preferences of the species, and their known summer–autumn occurrence in VIC waters it is likely they would migrate out of VIC waters before they reach the legal minimum length. As such, benefits to VIC anglers would be expected to be limited, and heavily dependent on uncertain return migrations of stocked fish.